Chronic neck pain ascribed to whiplash injury is a significant and costly problem. The longest study assessing the long-term effects of whiplash injury resulting from a motor vehicle collision showed that 55% of the participants had residual sequelae 17 years later (8). Most of these patients were continuing to receive some type of ongoing treatment.

There is no standard approach to the treatment of the patient who has sustained a cervical spine soft-tissue whiplash injury. One of the significant controversies concerns the use of the soft collar in the management of the acute phase of cervical spine soft tissue whiplash-injured patient. Presented here is a series of studies that have directly or indirectly assessed this issue. These studies often contrast the value of the cervical soft collar to the value of early mobilization in the management of these patients.

To begin, here is a review of the general principles of healing of injured soft tissues. A comprehensive review of the literature on the topic was published in October 1986 by Australian physician, John Kellett, MD. His review appeared in the journal Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise (1), and is titled:

Acute soft tissue injuries—

A review of the literature

In this article, Dr. Kellett describes the pathological processes of soft tissue injury and repair in three phases: acute inflammatory, repair, and remodeling, as follows:

Phase 1: The Acute Inflammatory or Reaction Phase

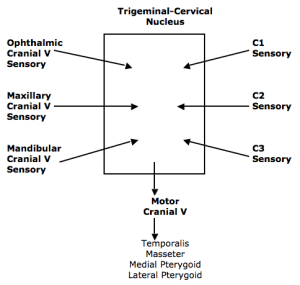

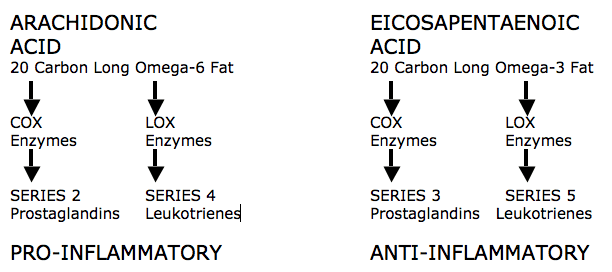

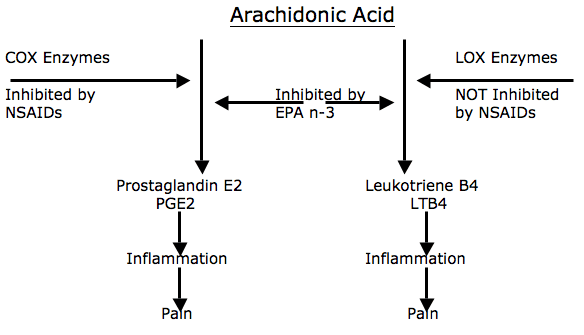

This phase lasts up to 72 hours. It is characterized by vasodilation, immune system activation of phagocytosis to remove debris, and the release of prostaglandins which cause inflammation. Prostaglandins also play a prominent part in pain production and increased capillary permeability (swelling). During this phase the wound is hypoxic, but macrophages can perform the phagocytosis duties anaerobically.

Phase 2: The Repair or Regeneration Phase

This phase lasts 48 hours to 6 weeks. It is characterized by the synthesis and deposition of collagen. The collagen that is deposited during this phase is not fully oriented in the direction of tensile strength, but rather laid down in an irregular pattern, different from that of the original tissue. This phase is “largely one of increasing the quantity of the collagen” but this collagen is not laid down in the direction of stress. Additionally, collagen fibers tend to contract between 3 and 14 weeks after injury, and perhaps for as long as 6 months, decreasing tissue elasticity.

Phase 3: The Remodeling Phase

This phase blends with the latter part of Phase 2, the Regeneration Phase, and may last up to 12 months or more. During this phase, the collagen is remodeled to increase the functional capabilities of the tendon or ligament to withstand the stresses imposed upon it. This phase is largely “an improvement of the quality” (orientation and tensile strength) of the collagen. It appears that the tensile strength of the collagen is quite specific to the forces imposed on it during the remodeling phase: i.e. the maximum strength will be in the direction of the forces imposed on the ligament.

This brief review by Dr. Kellett immediately suggests that immobilization of injured soft tissues would be detrimental to the healing process and that early mobilization would improve the timing and quality of healing. In fact, Dr. Kellett makes the following statements:

“Early mobilization, guided by the pain response, promotes a more rapid return to full activity.”

“Early mobilization, guided by the pain response, promotes a more rapid return to full functional recovery.”

“Progressive resistance exercises (isotonic, isokinetic, and isometric) are essential to restore full muscle and joint function.”

Dr. Kellett advocates the use of early mobilization, based upon the premise that the stress of movement on repairing collagen is largely responsible for the orientation and tensile strength of the tendons and ligaments. The stressing of repairing tissues with controlled motion induces adaptive response to functionally stronger connective tissues. According to Dr. Kellett, the benefits of early mobilization include:

1) Improvement of bone and ligament strength, which reduces recurrence of injury.

2) The strength of repaired ligaments is proportional to the mobility of the ligament, resulting in larger diameter collagen fiber bundles and more total collagen.

3) Collagen fiber growth and realignment is stimulated by early tensile loading of muscle, tendon, and ligament.

4) Collagen formation is not confined to the healing ligaments, but adheres to surrounding tissues. The formation of these adhesions between repairing tissues and adjacent structures is minimized by early movement.

5) With motion, “joint proprioception is maintained or develops earlier after injury, and this may be of importance in preventing recurrences of injuries and in hastening full recovery to competitive fitness.”

6) The nutrition to the cartilage is better maintained with early mobilization.

In contrast, Dr. Kellett notes that immobilization of soft tissue injuries decreases aerobic capacity, causes muscle wasting and loss of strength that may delay full recovery for a year or more.

At the microscopic level, Dr. Kellett notes that the healing of injured soft tissues usually contains granulation, fibrotic, or scar tissue. It is these poor quality-healing components that often account for residual reductions of strength and elasticity, impairing functional capacity and accounting for residual symptoms. Sports physicians Steven Roy and Richard Irvin note in their 1983 text titled Sports Medicine: Prevention, Evaluation, Management, and Rehabilitation (2) that early motion helps to prevent these fibrotic soft tissue changes. They state:

“The injured tissues next undergo remodeling, which can take up to one year to complete in the case of major tissue disruption. The remodeling stage blends with the later part of the regeneration stage, which means that motion of the injured tissues will influence their structure when they are healed. This is one reason why it is necessary to consider using controlled motion during the recovery stage. If a limb is completely immobilized during the recovery process, the tissues may emerge fully healed but poorly adapted functionally, with little chance for change, particularly if the immobilization has been prolonged. Another reason for encouraging controlled motion is that any adhesions that develop will be flexible and will thus allow the tissues to move easily on each other.”

Additional support for early mobilization in the management of soft tissue injuries is from physician James Cyriax. In his 1982 text Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, Dr. Cyriax states (3):

“Tension within the granulation tissue lines the cells up along the direction of stress. Hence, during the healing of mobile tissues, excessive immobilization is harmful. It prevents the formation of a scar strong in the important direction by avoiding the strains leading to due orientation of fibrous tissue and also allows the scar to become unduly adherent, e.g. to bone.”

••••

In 2000, physician Pekka Kannus, MD, PhD, adds to the understanding of the healing of inured soft tissues by employing immobilization or early mobilization. Dr. Kannus is chief physician and head of the Accident and Trauma Research Center and sports medicine specialist at the Tampere Research Center of Sports Medicine at the UKK Institute in Tampere, Finland. His article on the subject was published in the journal The Physician and Sports Medicine, and titled (4):

Immobilization or Early Mobilization

After an Acute Soft-Tissue Injury?

In this article, Dr. Kannus states:

“Experimental and clinical studies demonstrate that early, controlled mobilization is superior to immobilization for primary treatment of acute musculoskeletal soft-tissue injuries and postoperative management.”

“The current literature on experimental acute soft-tissue injury speaks strongly for the use of early, controlled mobilization rather than immobilization for optimal heating.”

“Controlled clinical trials of acute soft-tissue injuries support the results of experimental studies and have shown that early controlled mobilization is superior to immobilization, not only in primary treatment, but also in postoperative management.”

“The superiority of early controlled mobilization has been especially clear in terms of quicker recovery and return to full activity without jeopardizing the subjective or objective long-term outcome.”

“Evidence has been systematic and convincing for many injuries.”

Importantly, Dr. Kannus indicates that in animal studies, immobilization for longer than one week resulted in marked atrophy of the injured muscle. This article, adds to the support for using early mobilization following soft tissue injury and avoiding immobilization.

••••

In 1986, orthopedist K Mealy and colleagues specifically looked at the clinical outcomes of patients who received a cervical collar versus early mobilization for the treatment of acute soft tissue whiplash injuries. They published their study in the British Medical Journal in an article titled (5):

Early Mobilization of Acute Whiplash Injuries

This study is a prospective randomized trial where 61 consecutive patients with acute whiplash injuries were randomized to receive active treatment (31 patients) or standard (cervical collar) treatment (30 patients). The group assigned to receive active treatment received applications of ice in the first 24 hours and then neck mobilization and daily exercises of the cervical spine. Daily exercises were performed every hour at home, within the limits of pain; no analgesia was needed for this mobilization treatment or the exercises. The group given standard treatment received a soft cervical collar and was advised to rest for two weeks before beginning gradual mobilization. Their findings are summarized below:

“Though pain in both groups was similar initially, pain in the group given active treatment was significantly less than that in the group given standard treatment at both four weeks and eight weeks.”

“Movement increased significantly in the group given active treatment at four weeks and eight weeks.” “At eight weeks movement in the group given active treatment was significantly greater than that in the group given standard treatment.”

“Many patients with whiplash injuries present late, after a period of immobility, with persistent pain and stiffness.”

“We found that patients who are treated actively show significantly greater improvement in both cervical movement and intensity of pain compared with patients treated in the standard way.”

“At four weeks a significant increase in cervical movement occurred in the patients given active treatment but not in those given standard treatment. At eight weeks cervical movement was significantly greater in the patients given active treatment than those given the standard treatment, indicating that the increase in cervical mobility occurred earlier and to a significantly greater degree with active treatment.”

“At both four and eight weeks the improvement in pain was significantly greater in the group given active treatment, so that these patients had significantly less pain at four and eight weeks compared with the patients given standard treatment.”

“In conclusion, our results confirmed expectations that initial immobility after whiplash injuries gives rise to prolonged symptoms whereas a more rapid improvement can be achieved by early active management without any consequent increase in discomfort.”

This article is the first prospective randomized clinical trial addressing the outcomes of whiplash-injured patients who are treated with a cervical collar or with early mobilization. Clearly, early mobilization was superior to the cervical collar in this study.

••••

Physical therapist Mark Rosenfeld and colleagues published another study specifically evaluating the outcomes of whiplash-injured patients with either a cervical collar or with early mobilization. Their study appeared in the journal Spine in 2000, and is titled (6):

Early Intervention in

Whiplash-Associated Disorders

A Comparison of Two Treatment Protocols

This study is a prospective randomized trial in 97 patients with a whiplash injury caused by a motor vehicle collision. The study evaluates early active mobilization versus a standard treatment protocol that included the use of a cervical collar. These patients were followed-up and reevaluated at six months.

Rosenfeld and colleagues indicate that there are three studies showing the detrimental effect of rest and use of a cervical collar in the treatment of whiplash-injured patients. Yet, this type of treatment is still commonly recommended to patients in the early management of whiplash injuries.

The active treatment group was instructed to perform gentle, active, small-range and amplitude rotational movements of the neck, first in one direction, then the other. The movements were repeated 10 times in each direction every waking hour.

The standard treatment group was told that a soft collar could provide comfort and prevent the neck from excessive movement. They were also instructed to begin performing active movements, two or three times daily a few weeks after the injury.

Improvements during the first 6 months after trauma in range of motion and pain level were compared between the groups. “Evaluation of the two treatment protocols showed that 6 months after treatment, the reduction in pain was greater for those receiving active treatment than in those receiving standard [cervical collar] treatment.” The authors state:

“The main finding in this study was that active treatment of WAD resulted in a significantly greater pain reduction than standard treatment.”

“It seems that active mobilization is important. The current result confirms that frequent active mobilization exercises decrease symptoms more than a gradual mobilization program. Thus, a soft collar for the first period after injury is not the best treatment for WAD.”

“In patients with WAD caused by a motor vehicle collision, early treatment with frequently repeated active submaximal movements combined with mechanical diagnosis and therapy is more effective in reducing pain than treatment with initial rest, recommendation of a soft collar, and a gradual introduction of home exercises.”

In this study by Rosenfeld and colleagues, once again, early mobilization was clearly superior to the cervical collar in the treatment of acute whiplash injury.

Importantly, Mark Rosenfeld and colleagues published a three-year prospective follow-up as to the clinical status of these original 97 patients. This study was also published in the journal Spine in 2003, and titled (8):

Active Intervention in Patients with Whiplash-Associated Disorders Improves Long-Term Prognosis:

A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial

At this three-year follow-up, the authors found that pain intensity and sick leave were significantly reduced if patients received active intervention compared to those treated with a cervical collar. In addition, only patients receiving early active intervention had a total cervical range of motion similar to that of matched unexposed individuals. The authors concluded:

“In patients with whiplash-associated disorders, active intervention is more effective in reducing pain intensity and sick leave, and in retaining/regaining total range of motion than a standard intervention [cervical collar].”

“The reduction of pain intensity was greater and the need for sick leave was lower for patients receiving active intervention than in those receiving the standard [cervical collar] intervention.”

“The main finding in this study was that active intervention in patients with whiplash associated disorders resulted in a significantly greater reduction in pain intensity, a greater chance to retain or regain cervical range of motion, and reduced sick leave compared with a standard intervention.”

“The main clinical implication is that patients with acute WAD 0, 1, or 2 should be instructed in self-mobilization as soon as possible.”

Rosenfeld and colleagues propose that the most effective active motion is rotational, which “encourages regional blood flow and facilitates the removal of exudate, thus allowing healing to occur by aiding nutrition of joint structures.” Cervical spine rotation mobilizes the nerve structures on the contralateral side, thus preventing scar tissue from forming adhesions that will later cause dysfunction. Rotation mobilization may also affect the possible inhibition of intraneural microvascular blood flow caused by compression.

••••

The most comprehensive and referenced guideline pertaining to whiplash disorders was published in the journal Spine in 1995, and is titled (9):

Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-associated Disorders: Redefining ‘Whiplash’ and its Management

A comprehensive summary of this Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-associated Disorders was published in the May, 1998 Spine State of the Art Reviews (11) by Task Force members Richard Leclaire, a physiatrist, and Guy Bouvier, a neurosurgeon. Both authors are from Montreal, Quebec, Canada. They review the history and details of the creation of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders. Both the original Task Force and its summary by Leclaire and Bouvier contain treatment guidelines. Pertaining to the use of cervical collars in the management of whiplash injury, they note that in the three randomized controlled trials cited, the groups receiving soft collars had delayed recovery in terms of pain rating and range of motion compared to the groups receiving mobilization. They state:

“Collars may promote inactivity, which can delay recovery in patients with WAD.”

They conclude that in the treatment of whiplash injuries, cervical collars should not be used for grade I whiplash associated disorders and that for grade II or III, cervical collars should be used for no more than 72 hours. Pertaining to rest, the authors state:

“The cumulative evidence suggests that prolonged periods of rest are detrimental to recovery from whiplash associated disorders.”

“Rest should not be prescribed for whiplash associated disorders I. Rest longer than 4 days should not be prescribed for whiplash associated disorders II and III.”

••••

In 2007, orthopedic surgeon Jerome Schofferman and colleagues published an evidence-based review of chronic whiplash disorders. Their articles appeared in the Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, and was titled (11):

Chronic whiplash and whiplash-associated disorders: An evidence-based approach

In this evidence-based review of the literature pertaining to whiplash injuries, Dr. Schofferman and colleagues make the following points:

1) Following a motor vehicle collision, up to 40% of patients with acute neck pain develop chronic neck pain.

2) Following a motor vehicle collision, up to 7% of patients become permanently partially or totally disabled.

2) The cervical facet joint is the most common source of chronic neck pain after whiplash injury, followed by disk pain. Some patients experience pain from both structures.

3) Treatment includes advising the patient to remain active.

4) Recovery rates from whiplash trauma are:

A)) 44% are not recovered at 3 months.

B)) 30% are not recovered at 6 months.

C)) 24% are not recovered at 12 months.

D)) 18% are not recovered at 24 months.

Dr. Schofferman and colleagues make the following prognostic points:

1) Compensation or litigation is not associated with an adverse prognosis.

2) Older age, female sex, radicular symptoms, multiple areas of pain, and being unprepared for impact are associated with a worse prognosis.

3) “There is no pre-injury personality that renders individuals more likely to develop chronic pain after whiplash.”

4) There are no psychosocial factors that are useful predictors of whiplash injury chronicity.

5) There is no correlation between initial psychological testing and whiplash chronicity.

6) In most instances, psychological problems are a “consequence rather than a cause of pain.”

7) “There was no difference in the prevalence of pre-injury psychological illness in those who did or did not return to work.”

8) “The strongest predictor of prolonged disability [after whiplash injury] was intensity of [initial] symptoms.”

9) Differences in speed between vehicles is not predictive of whiplash symptom chronicity.

10) “Multiple studies have demonstrated that personal injury litigation does not adversely affect the outcome of whiplash injury.”

11) Patients with more pain and more objective findings are more likely to file litigation claims.

12) There is no evidence for symptom improvement after litigation is settled.

Dr. Schofferman and colleagues indicate that treatments for acute neck pain include remaining active despite ongoing pain, performance of prescribed exercises, and possible inclusion of spinal manipulation, which can improve outcomes over exercise alone.

In the treatment of chronic neck pain, “exercise alone is rarely curative” but exercise is helpful, and should be prescribed. The exercise should be directed to strengthen the weak muscle groups, usually the anterior, posterior, and interscapular muscle groups. Strength training is superior to stretching exercises, and intense exercise is superior to light exercise.

Spinal manipulation is one of the most popular treatments for chronic neck pain, and it can be beneficial. Serious complications from spinal manipulation are “quite low.”

Lastly, Dr. Schofferman and colleagues state that cervical collars are of “no value in the patient with acute whiplash injury.”

••••

The modern chiropractor is extensively trained in the application of early mobilization, exercise, and manipulation techniques to properly manage both the acute and chronic whiplash-injured patient. The application of these management techniques include:

1) Dispersion of the accumulation of inflammatory exudates that increase pain. This accelerates the timing of the healing process.

2) Puts controlled motion into the developing granulation tissue. This helps in the alignment of the tissues in the directions of stress and strain. This improves the quality of the end product of healing, reducing the chances that future increased stress will result in an exacerbation of signs and symptoms.

3) Reduces the formation of adhesions that often cause prolonged disability after soft tissue injury and healing.

REFERENCES:

- Kellett J; Acute soft tissue injuries–a review of the literature; Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise; October 1986;18(5):489-500.

- Roy, Steven, M.D., and Irvin, Richard, Sports Medicine: Prevention, Evaluation, Management, and Rehabilitation, Prentice-Hall, Inc. (1983).

- Cyriax, James, M.D., Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, Bailliere Tindall, Vol. 1, (1982).

- Pekka Kannus, MD, PhD; Immobilization or Early Mobilization After an Acute Soft-Tissue Injury? The Physician And Sports Medicine; March, 2000; Vol. 26 No 3, pp. 55-63.

- K Mealy, H Brennan, GCC Fenelon; Early mobilisation of acute whiplash injuries; British Medical Journal; Vol. 292, March 8, 1986, pp 656-657.

- Mark Rosenfeld; Ronny Gunnarsson; Peter Borenstein; Early Intervention in Whiplash-Associated Disorders: A Comparison of Two Treatment Protocols; Spine, 2000;25:1782-1787.

- Bunketorp L, Nordholm L, Carlsson J. A descriptive analysis of disorders in patients 17 years following motor vehicle accidents. European Spine Journal, 2002; 11: 227-34.

- Mark Rosenfeld, RPT; Aris Seferiadis, RPT; Jane Carlsson, RPT, PhD; Ronny Gunnarsson, MD, PhD; Active Intervention in Patients with Whiplash-Associated Disorders Improves Long-Term Prognosis: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial; Spine 2003; 28(22):November 15, 2003; 2491-2498.

- Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR; Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-associated Disorders: Redefining ‘whiplash’ and its management; Spine; April 15, 1995, 20 (supplement 8): 1S-73S.

- Leclaire R, Bouvier G, A summary of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: Classification, evaluation, and treatment guidelines, Spine State of the Art Reviews, Vol. 12, No. 2, 1998, 271-286.

- Schofferman J, Bogduk N, Slosar P. Chronic whiplash and whiplash-associated disorders: An evidence-based approach; Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; October 2007;15(10):596-606.