Safety, Effectiveness, Outcomes

Biomechanics 101

Humans are both mechanical (they obey the laws of physics) and biological (they obey the laws of biology). The blending of the laws of mechanics and biology are referred to as biomechanics. Humans are biomechanical.

A simple concept in biomechanics is that there is a trade-off between mobility and stability. The regions of the body that have the greatest mobility also have the least stability and are thus the regions that are most vulnerable to injury. Stated differently, the regions of the body that have high stability tend to have reduced mobility and a reduced risk for injury.

The region of the spinal column that has the least stability and hence the greatest mobility is the upper cervical spine. The upper cervical spine has the greatest risk of injury of the entire spinal column.

•••••

For more than a century, chiropractic pioneers have studied and developed practical approaches for the management of upper cervical spine biomechanical problems. The current academic leader for the understanding of upper cervical spine biomechanics and their clinical approaches is Kirk Eriksen, DC, from Dothan, Alabama, where he is in private clinical practice. In 2004, Dr. Erikson authored a book, titled (1):

Upper Cervical Subluxation Complex:

A Review of the Chiropractic and Medical Literature

This incredible review was published by a major scientific/medical publishing house, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

In 2011, Dr. Erikson was also the lead author of an article published in the journal BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, titled (2):

Symptomatic Reactions, Clinical Outcomes and Patient Satisfaction Associated with Upper Cervical Chiropractic Care:

A Prospective, Multicenter, Cohort Study

In this publication the authors indicate that little research is available on the topic of side effects resulting from upper cervical chiropractic techniques. This study was the first prospective study to examine the incidence of adverse reactions following spinal adjustments using upper cervical techniques. The authors also assessed the impact of upper cervical chiropractic care on clinical outcomes.

The authors assessed 1,090 consecutive new patients (8 to 85 years of age) from 83 chiropractic offices. Seventy of the chiropractors were from the United States, eleven were from Canada, and two were from Europe (one from England and one from Spain). The mean years in clinical practice by these chiropractors was 13.0.

The 1,090 patients had 4,920 chiropractic office visits and 2,653 upper cervical adjustments over a 17-day period. The average number of career adjustments per chiropractor was 61,265 with a total of 5,085,011 career adjustments for all participating upper cervical chiropractors. Importantly:

“The doctors did not report any serious adverse events ever occurring in their practices (i.e., strokes or permanent injuries).”

The authors made an explicit distinction between a “symptomatic reaction” vs. a “serious adverse event, which refers to events resulting in death, life-threatening situations, need for admittance to a hospital, or temporary or permanent disability.”

In this study, the only chiropractic intervention was upper cervical spine chiropractic adjustments (specific line-of-drive manipulations). There was no physical therapy or spinal adjusting below the upper cervical spine.

Eighty-one percent of the patients in this study had as their primary complaint either spinal pain/dysfunction and/or headaches. Seventy-four percent of cases were chronic, with symptoms being persistent for more than 13 weeks. The entire breakdown of patient symptoms included:

| Cervical pain/dysfunction | 35% |

| Lumbo-pelvic pain | 28% |

| Headaches | 13% |

| Mid-back pain | 5% |

| Lower extremity pain | 4% |

| Shoulder pain | 3% |

| Upper extremity | 2% |

| Fibromyalgia | 2% |

| Disequilibrium | 2% |

| Temporomandibular joint pain | 1% |

| Facial pain/dysfunction | 1% |

| Blood pressure | 1% |

| Neurological disease | 1% |

| Brain dysfunction | 1% |

| Wellness care | 1% |

| Other complaints with < 0.5% occurrence: atopic disorders, diabetes, ear, GI dysfunction, hypothyroidism, Lyme’s disease, postural distortion, psoriatic arthritis, psychological disorders, sinus problems, sleep disorders, thorax dysfunctions, visual disturbance, autoimmune disorder, irregular menstrual cycle, and weak immune system. | |

The adjustments in this study were administered by hand, a hand-held instrument, or table mounted instruments. Hand adjustments were delivered in 67% of cases, while 33% were adjusted by instrument.

The primary symptoms assessed were neck pain, headache, mid back pain and/or low back pain. The clinical outcome measurement tools included:

- Neck pain disability index (NDI)

- Oswestry disability index (ODI)

- 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS) for neck, headache, midback, and low back pain

- Treatment satisfaction

- Symptomatic Reactions (SR)

The authors stated:

“The patient rated their overall neck, headache, mid back and/or low back pain using a written 11-point Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), for applicable complaints (0 = no pain, 10 = the worst possible pain).”

“To assess the impact of the patient’s pain on their ‘activities of daily living’ the patient completed a Neck Disability Index (NDI) and/or Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), depending on whether the subject had symptoms in the neck or back, respectively.”

“The NDI and ODI have been demonstrated to be reliable and valid instruments.”

“Patient satisfaction was measured at the end of the treatment period by a question that asked, ‘How satisfied are you with the treatment by your chiropractor?’”

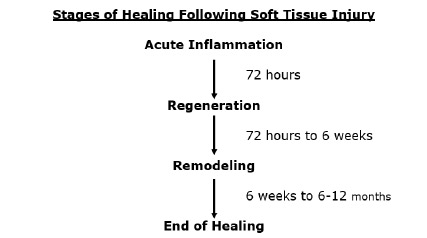

A symptomatic reaction (SR) was defined as a new complaint that was not present at baseline or a worsening of the presenting complaint by >30% based on an 11-point numeric rating scale occurring <24 hours after any upper cervical procedure. The assessment included distinguishing between a symptomatic reaction and “soreness” which “could represent change or healing.”

The authors recognize that upper cervical chiropractic techniques have been used by chiropractors and taught in chiropractic colleges since the 1930s. All upper cervical chiropractic techniques originate from BJ Palmer, the person credited with the development of chiropractic as a separate and distinct profession.

The assessment tools used by these chiropractors included a combination of x-ray alignment, postural distortion, palpatory tenderness, range of motion, and/or paraspinal thermometry (temperature reading devices).

The upper cervical techniques reviewed in this study included:

- Atlas/Advanced Orthogonal – “Atlas Orthogonality was founded by Roy Sweat, DC in 1981. Advanced Orthogonality was founded by Stan Pierce, DC in 2001. Both procedures use a side posture patient position with a solid mastoid support, segmental contact over and directed toward the C1 transverse process via a stationary stylus on a table mounted instrument. The force is on a specific pre-calculated vector generated by a percussion wave mechanism.”

- Blair – “Blair technique was founded by Williams Blair, DC in 1960. This technique uses a side posture patient position on a drop headpiece toggle table, with the surface of the headpiece parallel to the floor. The doctor contacts the patient with his pisiform over the anterior, posterior, or inferior transverse process based upon the necessary correction. With the headpiece cocked, a toggle and 180° torque type correction is administered depending on predetermined vertebral alignment variables.”

- Knee Chest – “Knee Chest technique has been in use since BJ Palmer, DC developed UC chiropractic in 1931. The patient is in a kneeling position with their head turned on a solid headpiece table. Segmental contact point is over the posterior arch and uses a toggle-torque-recoil type thrust.”

- National Upper Cervical Chiropractic Association (NUCCA) – “NUCCA was founded by Ralph Gregory, DC in 1966. This procedure uses a side posture patient position with a solid mastoid or skull support. The segmental contact is over the C1 transverse process via the pisiform using a hand adjustment. The force is on a specific pre-calculated vector generated by a triceps pull.”

- Orthospinology/Grostic Procedure – “The Grostic Procedure was developed by John F. Grostic, DC in the late 1930s. Orthospinology was founded by a group of doctors in 1977 that implemented instrument adjusting as well as manual adjusting. Both procedures use a side posture patient position with a solid mastoid support. The segmental contact is over and directed toward the C1 transverse process via a moving stylus on a table mounted or hand-held instrument or via the pisiform using a hand adjustment. The force is a single pulse on a specific pre-calculated vector generated by a solenoid or a manual cam accelerated mechanism for instruments or a triceps pull for hand adjustments.”

- Spinal Orthopedic Neurological Advancement and Research (SONAR) – “SONAR was developed by Thomas Elliott, Jr., DC who was a NUCCA practitioner. SONAR employs procedures for taking and analyzing x-rays. The SONAR instrument uses computer generated specific sound waves in a precise vector of the size, magnitude and torque required to reposition the upper cervical spine.”

- Toggle Recoil/Duff – “Toggle Recoil was popularized in the 1930s by BJ Palmer, DC with his development of HIO technique (which was also done in the Knee Chest position)… This type of adjustment is made in the side posture patient position on a drop headpiece toggle table, with the doctor’s pisiform contact over the C1 transverse process. A quick contraction and relaxation of the triceps generates the administered force… The Duff Method of Analysis was developed by Stephen A. Duff, Sr. DC, and utilizes a specific pre/post thermographic instrumentation procedure and upper cervical x-ray analysis. The adjustive technique utilizes a modified toggle-recoil to the atlas or axis with a predetermined vector and contact point. A side posture table with a drop mechanism is used.”

The authors specifically address the alleged association between cervical manipulation and cerebrovascular incidents. They state and reference these statistics:

“Estimated occurrence ranging from no causative association, to 1 in 300,000 to 500,000 to 1.3 million to 5.85 million cervical manipulations.”

“[A study has] found that the risk of having a stroke was equal between patients consulting a chiropractor or general medical practitioner.”

“This suggests that cervical manipulation may not be a cause of cerebrovascular accidents, but associated with a stroke in progress.”

The outcomes from this study were quite good:

- Neck pain improved by a mean of 57% and 62% of the total sample had become asymptomatic.

- Headache pain improved by 63%.

- Thoracic pain improved by 59%.

- Lumbar pain improved by 57%.

- Neck disability (NDI) improved by 47%.

- Low back disability (ODI) improved by 45%.

The authors stated:

“Outcome assessments were significantly improved for neck pain and disability, headache, mid-back pain, as well as lower back pain and disability following care with a high level (mean = 9.1/10) of patient satisfaction.”

“Upper cervical chiropractic care may have a fairly common occurrence of mild intensity SRs short in duration (<24 hours), and rarely severe in intensity; however, outcome assessments were significantly improved with less than 3 weeks of care with a high level of patient satisfaction.” “[All of these symptoms were] mild intensity, short duration and little effect on daily living.”

“Non-musculoskeletal responses included ‘easier to breathe,’ ‘improved digestive function,’ ‘improved vision,’ and ‘improved circulation.’”

The authors concluded:

“Chiropractic care using upper cervical techniques may have a fairly common occurrence of mild intensity SRs short in duration (<24 hours), and rarely severe in intensity; however, outcome assessments were significantly improved with less than 3 weeks of care with a high level of patient satisfaction.”

“Patients reported a very high degree of satisfaction with upper cervical techniques chiropractic care scoring a mean of 9.1/10 using an 11-point NRS.”

“The preponderance of the evidence shows that major complications resulting from chiropractic care are very rare, although transient discomfort and other minor side effects of chiropractic care are common.”

“Local discomfort in the treatment area accounts for half to two thirds of the reactions.”

The majority of reactions began within 24 hours of the treatment visit and resolved in less than 24 hours.

The Upper Cervical Spine and “The Cork” of Cerebrospinal Fluid

A greater understanding of the biomechanics and pathoanatomy of the upper cervical spine has been advanced by the use of upright weight-bearing MRI (3, 4, 5). This enhanced understanding helps to explain the clinical benefits of upper cervical spine chiropractic care (2). The evidence and the follow-up theories are as follows:

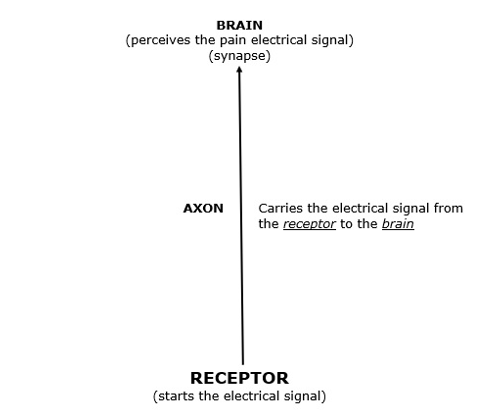

The physiology and health of the brain and spinal cord is dependent upon the flow of cerebral spinal fluid. The cerebral spinal fluid is generated in the brain and circulates throughout the brain and the spinal cord, literally bathing these neurological structures in the nutrient-rich fluid. To get to the spinal cord, the cerebral spinal fluid must pass through a hole in the skull, the foramen magnum. The top of the spinal column also has a hole through which the cerebral spinal fluid must flow, the atlas vertebrae, also known as cervical-1 or C-1.

A biomechanical misalignment between the foramen magnum hole and the atlas vertebrae hole may impair the flow of cerebral spinal fluid between the skull and the spine (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 ). The consequence of this includes an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the skull. This skull fluid accumulation is easily verified with MRI technology (4, 5).

This model of skull-atlas misalignment impairment of cerebral spinal fluid flow causing increased cerebral spinal fluid pressures in the brain is associated with symptomology and dysfunction. The benefits of upper cervical spine chiropractic adjusting is gaining scientific support and media attention.

Quarterback Jim McMahon

Jim McMahon was a great football quarterback. He was born in 1959. He played college football at Brigham Young University, earning All-American status in 1980 and 1981. The Chicago Bears drafted him in the first round of the NFL draft in 1982.

In 1982, McMahon was UPI NFC Rookie of the Year. He earned a Pro Bowl appearance in 1986, and two Super Bowl Rings. He appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated numerous times (10). McMahon retired in 1996 at the age of 37 years.

Sixteen years after he retired from football, at age 53, McMahon appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated (September 10, 2012 issue) once again (11). It was an article detailing his struggles with dementia, headaches, and other behavior/health problems.

In 2016, Jim McMahon was profiled in an ESPN Special Report as a consequence of a change in his clinical status. The signs and symptoms of his chronic neurodegenerative disorder had quickly and dramatically improved (12).

An upright weight-bearing MRI was taken of McMahon’s head and neck. As noted above, the imaging showed an accumulation of fluid (cerebrospinal fluid) in his skull and around his brain. McMahon’s upper cervical chiropractor documented a meaningful malalignment between the skull and the atlas vertebra. Such a finding is consistent with an impairment of cerebrospinal fluid flow.

McMahon’s chiropractor carefully and precisely adjusted his atlas vertebra with respects to the skull with the ideal goal of establishing perfect alignment between the occiput and the atlas vertebrae. This goal was achieved, verified by post-adjustment radiographs. The improvement in McMahon’s signs and symptoms were essentially instantaneous. A post adjustment upright weight-bearing MRI of McMahon’s brain and spinal cord showed a remarkable reduction of fluid accumulation. The entire procedure was taped and aired on ESPN.

This McMahon story has been picked-up by the lay press, including the Sacramento Bee in 2016 (13) and the San Francisco Chronicle in 2017 (14). Both stories appeared in the sports pages following interviews with McMahon during celebrity golf outings.

•••••

The indexed, peer-reviewed, scientific literature is also supporting the “cork” hypothesis as a consequence of misalignment between the skull and the atlas. These studies are referenced above and briefly reviewed below:

In 2011, a study appeared in the journal Physiological Chemistry and Physics and Medical NMR, titled (4):

The Possible Role of Cranio-Cervical Trauma and Abnormal CSF Hydrodynamics in the Genesis of Multiple Sclerosis

The primary author, Raymond Damadian, MD, was famous (now deceased). According to his obituary in The Wall Street Journal (August 28, 2022), Dr. Damadian was the discoverer of the technology behind MRI (15).

In this study, eight multiple sclerosis (MS) patients and seven normal volunteers were MRI scanned to visualize the overall cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow pattern. Abnormal CSF flows were found in all eight MS patients. None of the normal volunteers had these flow obstructions. These authors note:

“The abnormal CSF flows corresponded with the cranio-cervical structural abnormalities found on the patients’ MR images.”

“The abnormal CSF flow dynamics found in the MS patients of this study corresponded to the MR cervical pathology that was visualized.”

This study is particularly important for chiropractors. These authors suggest that cervical spine malalignment obstructs the flow of cerebral spinal fluid. This obstruction of CSF flow increases intracranial pressure, leading to brain pathology dysfunction. These authors suggest that the improvement in cranial-cervical malalignment could improve cerebral spinal fluid flow.

•••••

In 2015, another supportive study appeared in the journal Neurology Research International, titled (8):

The Role of the Cranio-cervical Junction in Cranio-spinal Hydrodynamics and Neurodegenerative Conditions

The author notes that cranio-spinal hydrodynamics refers to the relationship between blood and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) volume, pressure, and flow in the relatively closed confines of the compartments of the cranial vault and spinal canal. He notes that cranio-spinal hydrodynamics can be disrupted by a number of mechanical lesions (congenital, degenerative, and acquired) of the cranio-cervical junction (CCJ), stating:

“The CCJ links the vascular and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) systems in the cranial vault to those in the spinal canal.”

“The cranio-cervical junction (CCJ) is a potential choke point for cranio-spinal hydrodynamics and may play a causative or contributory role in the pathogenesis and progression of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and ALS, as well as many other neurological conditions including hydrocephalus, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, migraines, seizures, silent-strokes, affective disorders, schizophrenia, and psychosis.”

“Malformations and misalignments of the CCJ cause deformation and obstruction of blood and CSF pathways and flow between the cranial vault and spinal canal that can result in faulty cranio-spinal hydrodynamics and subsequent neurological and neurodegenerative disorders.”

These authors are quite clear: an acquired blockage to CSF flow, important to chiropractors, is a misalignment of the atlas on the occipital condyles. They emphasize that the cranial-cervical junction is a choke point for cerebral spinal fluid flow between the cranial vault and spinal canal. They believe that manual/mechanical care may correct cranial-cervical junction structural problems, improving faulty cranio-spinal hydrodynamics and symptoms.

•••••

In 2015, the most authoritative book written to date detailing the pathogenic potential, diagnosis, and treatment of cranio-cervical junction alignment problems was published (5). The reference book is titled The Craniocervical Syndrome and MRI. The editors are professor Francis W. Smith (London) and physician Jay S. Dworkin (New York). These important points are expressed:

“Upright MRI provides the decisive utility of cerebrospinal fluid flow studies around the craniocervical junction.”

“Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is conveniently performed in the supine position, in which noinformation about the effect of gravity on the patient in the upright position is possible.” [emphasis added]

“MRI may show CSF accumulation.”

“C1 misalignment may contribute to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow obstruction.”

“Craniocervical junction misalignments can compromise the normal flow of spinal fluid in and out of the cranial vault.”

“Craniocervical junction misalignments can cause headaches, neck pain (skull base pain), nausea, dizziness, tinnitus and facial pain, to name a few.”

Summary

Upper cervical specific chiropractic techniques have been an important part of the profession for more than a century. Traditionally, the alignment assessment involves some type of precise imaging. Upper cervical chiropractors tend to have similar treatment goals: as perfect as possible alignment between the skull and the atlas. Yet, there is quite a variance as to the adjustment approaches used to make the correction, all of which have their proponents. Most chiropractors consider upper cervical specific care to be a unique specialty within the chiropractic profession. Upper cervical chiropractic care offers a unique benefit for a range of clinical syndromes.

REFERENCES

- Eriksen K; Upper Cervical Subluxation Complex: A Review of the Chiropractic and Medical Literature; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.

- Eriksen K, Rochester RP, Hurwitz EL; Symptomatic Reactions, Clinical Outcomes and Patient Satisfaction Associated with Upper Cervical Chiropractic Care: A Prospective, Multicenter, Cohort Study; BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders; October 5, 2011; Vol. 12; No. 219.

- Freeman MD, Rosa S, Harshfield D, Smith F, Bennett R, Centeno CJ, Kornel E, Nystrom A, Heffez D, Kohles SS; A case-control study of cerebellar tonsillar ectopia (Chiari) and head’neck trauma (whiplash); Brain Injury; 2010; Vol. 24; Nos. 7-8; pp. 988-994.

- Damadian RV, Chu D; The Possible Role of Cranio-Cervical Trauma and Abnormal CSF Hydrodynamics in the Genesis of Multiple Sclerosis; Physiological Chemistry and Physics and Medical NMR; September 20, 2011; 41; pp. 1–17.

- Smith FW, Dworkin JS; The Craniocervical Syndrome and MRI; Karger; 2015.

- Deltoff MN; “Diagnostic Imaging of the Cranio-Cervical Region”, Chapter 4, in The Cranio-Cervical Syndrome, Mechaniscm, Assessment and Treatment; Edited by Howard Vernon; Butterworth Heinemann; 2003.

- Flannagan MF; The Downside of Upright Posture: The Anatomical Causes of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Multiple Sclerosis; Two Harbors Press; 2010.

- Flanagan MF;The Role of the Cranio-cervical Junction in Cranio-spinal Hydrodynamics and Neurodegenerative Conditions; Neurology Research International; November 30, 2015; Article 794829.

- Flannagan MF; Hydrodynamics in Neurodegenerative and Neurological Disorders; Nova; 2016.

- Hendricks M; Super Bowl-winning quarterback Jim McMahon says he wishes he had played baseball; Yahoo!; September 27, 2012.

- Segura M; The Other Half of the Story; THE WOMEN BEHIND THE MEN; Sports Illustrated; September 10, 2012.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ZxIUz4sc0U

- Furillo A; Shoeless Golf is a Perfect Fit for McMahon; Sacramento Bee; July 21, 2016; pp. 1C and 5C.

- Ostler S; Quarterbacking a Gypsy Lifestyle, Renewed Outlook for Former NFL Star; San Francisco Chronicle, July 15, 2017; pp. B1 and B7.

- Hagerty JR; Raymond Damadian, 1936-2022: Doctor Pioneered MRI Scanning; The Wall Street Journal; August 28, 2022.