Terminology Update

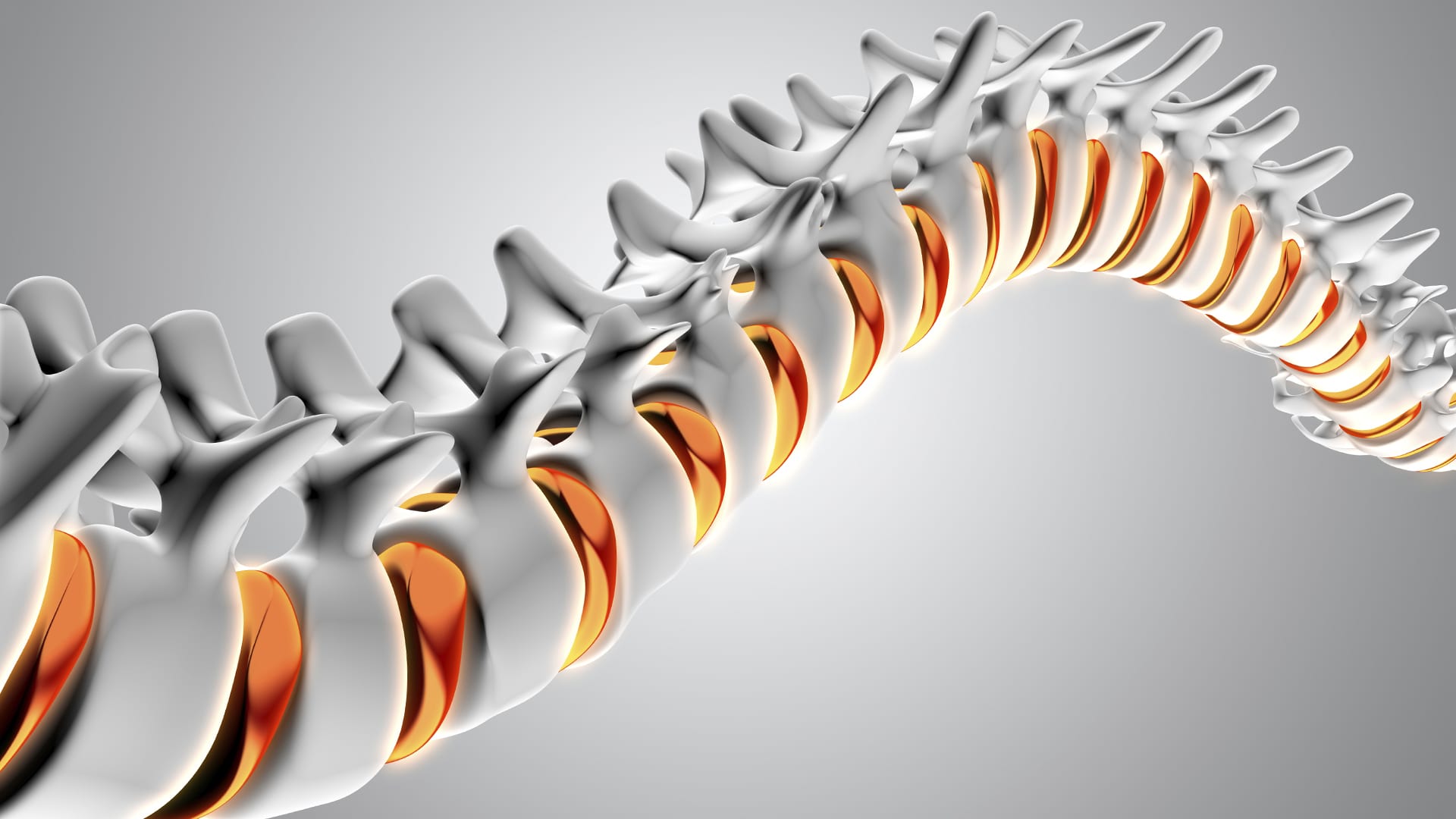

The terminology pertaining to lumbar spinal disk herniations has been confusing, inconsistent, and contradictory. Consequently, in 2014, the North American Spine Society, the American Society of Spine Radiology, and the American Society of Neuroradiology convened a combined task force to agree upon the nomenclature. The results were published in the Spine Journal, and titled (1):

Lumbar Disc Nomenclature:

Version 2.0

In summary, and based on CT or MRI imaging, a herniated lumbar spine intervertebral disk has four categories:

- Bulging Disk

- Protrusion Disk

- Extrusion Disk

- Sequestration Disk

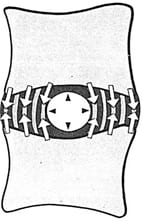

The Normal Disk

The Bulging Disk

If any part of the annulus extends beyond the normal disc space, it is considered to be a bulging disk.

The Protrusion Disk

In the protrusion disk, the base of the displaced material is greater than the distance the disk material had moved towards the intervertebral foramen and/or the central neural canal.

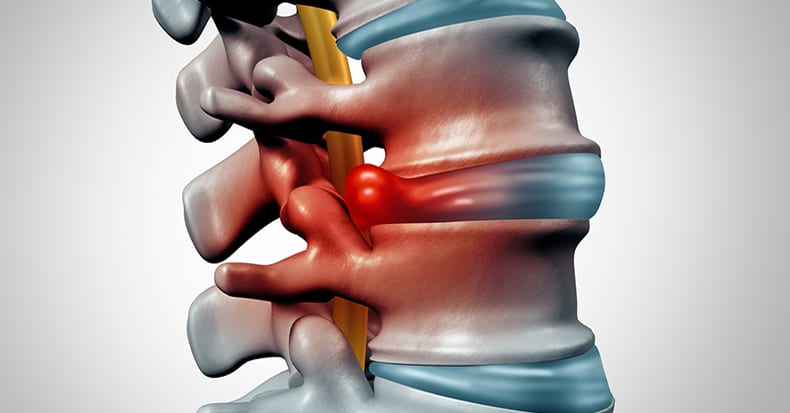

The Extrusion Disk

In the extrusion disk, the greatest measure of the displaced disk material is greater than the measure of the base of the displaced material.

The Sequestration Disk

In the sequestration disk, the disk material has lost all connection with the original disk material.

••••••••••

A disk herniation that compresses, irritates or inflames a single nerve root is called discogenic radiculopathy. Nerve root compression/irritation/inflammation can cause radiating leg pain down the course of the sciatic nerve. Consequently, this radiating leg pain is often referred to as sciatica. If this sciatica is initiated by the intervertebral disk, it is referred to as discogenic sciatica.

Technically, the sciatic nerve is made up of nerve roots L4, L5, S1, and as such a problem with any of these nerve roots can cause sciatica.

If the intervertebral disk is the cause of the nerve root compression/irritation/inflammation, the single most important clinical test is the straight-leg-raising test. While supine, the subject is asked to raise their straight leg as far as possible. Normally this causes the lower lumbar nerve roots to slide out of the intervertebral foramen by approximately ½ inch (12 mm). If the nerve root is compressed/irritated/inflamed, pain may start at about 30 degrees from the horizontal (2, from Kapandji).

Important questions pertaining to herniated lumbar intervertebral disc with radiculopathy/sciatica include:

- What are the typical presenting symptoms for patients suffering from discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica?

- What are the most important clinical tests for the patient with suspected discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica?

- Are spinal x-rays required or helpful in establishing the diagnosis of discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica?

- When is computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) advisable for a patient with suspected discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica?

- For how long is it advised and/or safe for the patient with discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica to have their signs and symptoms managed conservatively?

- How effective is conservative treatment for the discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica patient, as compared to surgical treatment?

- Is chiropractic spinal adjusting (specific manipulation) safe and effective for patients suffering from discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica?

The answers to many of these questions are thoroughly explored in an important article published May 5, 2016 in The New England Journal of Medicine, titled (3):

Herniated Lumbar Intervertebral Disk

The authors are Richard A. Deyo, MD, MPH, and Sohail K Mirza, MD, MPH. Dr. Deyo is from the Oregon Institute of Occupational Health Sciences. A search of the United Stated National Library of Medicine (June 12, 2016) shows he is an author or contributing author to 378 indexed publications. Dr. Mirza if from the Department of Orthopedic Medicine, Dartmouth School of Medicine. A search of the United Stated National Library of Medicine (June 12, 2016) shows he is an author or contributing author to 87 indexed publications. These men are leading experts on the clinical guidelines pertaining to the lumbar spine and intervertebral disk syndromes.

In this article, Drs. Deyo and Mirza make the following points:

- 2/3 of adults have back pain at some time in their lives.

- 10% of adults have back pain that has spread below their knees within the previous 3 months. Often, the sciatica occurs with “no specific precipitating event.”

- “The prevalence of herniated disks as the cause of back and leg pain may be approximately 10% in primary care.”

- Lumbar radiculopathy refers specifically to pain and motor and sensory disturbances in a nerve-root distribution.

- “Disk herniation does not necessarily cause pain; MRI commonly shows herniated disks in asymptomatic persons.”

- Genetic factors related to the structure of collagen may predispose the disk to degeneration.

- Strenuous activity and smoking are environmental factors that increase the risk of disk herniation.

- “Disk-related radiculopathy is both a biochemical and a biomechanical process.” “Contact of the nucleus pulposus with a nerve root provokes inflammation that may be necessary for mechanical compression to cause pain.” This inflammatory component to radiculopathy is recognized, and anti-inflammatory therapy is proposed. [This is important as it indicates that some patients will benefit or perhaps require anti-inflammatory adjuncts in the management of their discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica].

- 95% of herniated disks occur between L4-L5 (L5 nerve root) and L5-S1 (S1 nerve root).“The L5 nerve root affects neither the Achilles tendon nor the patellar reflex and is one of the two most commonly affected nerve roots.” Consequently in a person with L5 radiculopathy, tendon reflexes may convey no information.

- A “massive midline disk herniation may compress the cauda equina, causing cauda equina syndrome.” Cauda Equina Syndrome symptoms include sciatica, motor weakness, urinary incontinence or retention, saddle anesthesia, and diminished anal sphincter tone. [Cauda Equina Syndrome is a surgical emergency].

- “Electromyography is usually unnecessary.”

- The use of opioid drugs should be limited to patients with severe pain and should be time limited from the outset because of the lack of evidence of benefit and the “growing concern regarding serious long-term adverse effects.”

- Glucocorticoid injections for lumbar herniation with radiculopathy shows no significant advantage over placebo for pain relief or reduced rate of subsequent surgical intervention, nor does it show an advantage with respect to improvement in physical function.

- “In patients with acute disk herniations, avoidance of prolonged inactivity in order to prevent debilitation is important.”

- Most patients with acute disk herniations “can be encouraged to stand and walk.”

- “The ability to sit comfortably is a sign of improvement in the patient’s condition” and suggests more structured exercise may begin.

- Lifestyle modifications, including smoking cessation, weight loss, and regular exercise may prevent sciatica or help reduce its recurrence.

What are the typical presenting symptoms for

patients suffering from discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica?

Drs. Deyo and Mirza note that approximately 85% of patients with sciatica have a herniated intervertebral disk. Hence, sciatica is the single most important presenting symptom of discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica.

What are the most important clinical tests

for the patient with suspected discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica?

Drs. Deyo and Mirza note that the majority of patients “with back and leg pain and a positive straight-leg-raising test suggests a herniated disk.” Straight-leg-raising is positive for nerve root compression if sciatica occurs by elevating the leg to between 30 and 70 degrees.

Other helpful tests include deep tendon reflexes, superficial sensation, myotomal strength, and Valsalva tests.

Are spinal x-rays required or helpful in establishing

the diagnosis of discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica?

Spinal x-rays are not required or helpful in establishing the diagnosis of discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica. Spinal x-rays may show levels of disc degeneration of varying degrees, but are non-revealing as to the presence or type of disc herniation and compressive neuropathology. Spinal x-rays may show the presence of other complications to discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica, such as birth anomalies (tropism, lumbosacral transitional segments, scoliosis, leg length inequality, etc.) and/or acquired syndromes (degenerative osseous central canal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, fracture, etc.). Spinal x-ray may also show evidence of tumor and/or infection. As such, exposing spinal x-rays is dependent upon the clinical judgment of the provider.

When is computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) advisable for a patient with suspected discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica?

Drs. Deyo and Mirza do not recommend routine use of CT or MRI because “on imaging, disk bulging is common among asymptomatic persons (in approximately 60% of persons at 50 years of age).” They state:

“CT or MRI is necessary only in a patient whose condition has not improved over 4 to 6 weeks with conservative treatment.”

“The use of CT or MRI should be discouraged unless the symptoms do not decrease over 4 to 6 weeks” of conservative treatment.

For how long is it advised and/or safe for

the patient with discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica

to have their signs and symptoms managed conservatively?

Drs. Deyo and Mirza state:

Six weeks of conservative therapy is generally recommended in patients with herniated lumbar disks, in the absence of a major neurological deficit.

“Unless patients have major neurologic deficits, surgery is generally appropriate only in those who have nerve root compression that is confirmed on CT or MRI, a corresponding sciatica syndrome, and no response to 6 weeks of conservative therapy.”

In the absence of severe neurologic deficits, discogenic sciatica patients should have conservative treatment for 6 weeks before agreeing to more invasive approaches (glucocorticoids injections, surgery).

The mean time for resolution of discogenic sciatica symptoms with conservative care is 12 weeks.

Patients who first use conservative treatment for discogenic sciatica and later opt for surgery still do well, indicating an “absence of a therapeutic window for surgery that closed quickly.”

How effective is conservative treatment for the discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica patient, as compared to surgical treatment?

Drs. Deyo and Mirza state that most patients with radicular sciatica who do not undergo surgery will improve. They further note:

Conservative treatment does not change the natural history of disk herniation, but offers relief of symptoms. Most herniated disks will shrink with resolution of symptoms over 3-12 months.

Minor motor deficits will resolve in most patients who are treated conservatively.

“Elective surgery is an option for patients with congruent clinical and MRI findings and a condition that does not improve within 6 weeks.”

“Patients with severe or progressive neurologic deficits require a referral for surgery.”

There is “no significant advantage of surgery over conservative treatment for sciatica relief at 1 to 4 years of follow-up.”

“By 1 year, outcomes of early surgery generally do not differ from those of prolonged conservative therapy.”

Is chiropractic spinal adjusting (specific manipulation) safe and effective for patients suffering from discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica?

Drs. Deyo and Mirza clearly indicate that chiropractic spinal manipulation is both safe and usually effective in the management of patients suffering with discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica, stating:

A randomized trial of chiropractic manipulation for subacute or chronic back related leg pain “showed that manipulation was more effective than home exercise with respect to pain relief at 12 weeks.”

“A randomized trial involving patients who had acute sciatica with MRI-confirmed disk protrusion showed that at 6 months, significantly more patients who underwent chiropractic manipulation had an absence of pain than did those who underwent sham manipulations (55% vs. 20%).”

In addition, for many decades, published studies have supported the effectiveness and safety of spinal manipulation for the management of discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9). A recent study adding to the evidence is presented here (10).

In 2006, physicians Valter Santilli, MD, Ettore Beghi, MD, Stefano Finucci, MD published a study in the Spine Journal, titled (10):

Chiropractic manipulation in the treatment of

acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion:

A randomized double-blind clinical trial of

active and simulated spinal manipulations

The purpose of this study was to assess the short- and long-term effects of spinal manipulations on acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion. It is a randomized double-blind trial comparing active and simulated manipulations for these patients. The study used 102 patients. The manipulations or simulated manipulations were done 5 days per week by experienced chiropractors for up to a maximum of 20 patient visits, “using a rapid thrust technique.” Re-evaluations were done at 15, 30, 45, 90, and 180 days. Sixty-four men and 38 women were randomized to manipulations (n=53) or simulated manipulations (n=49).

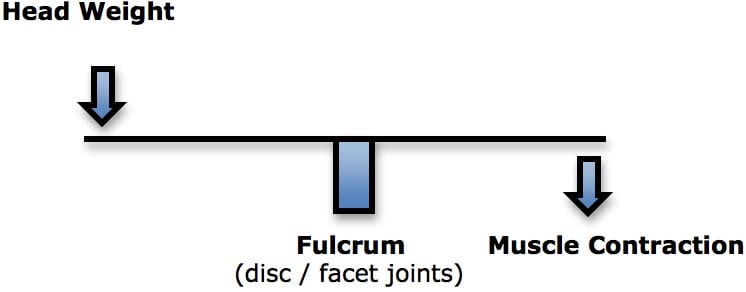

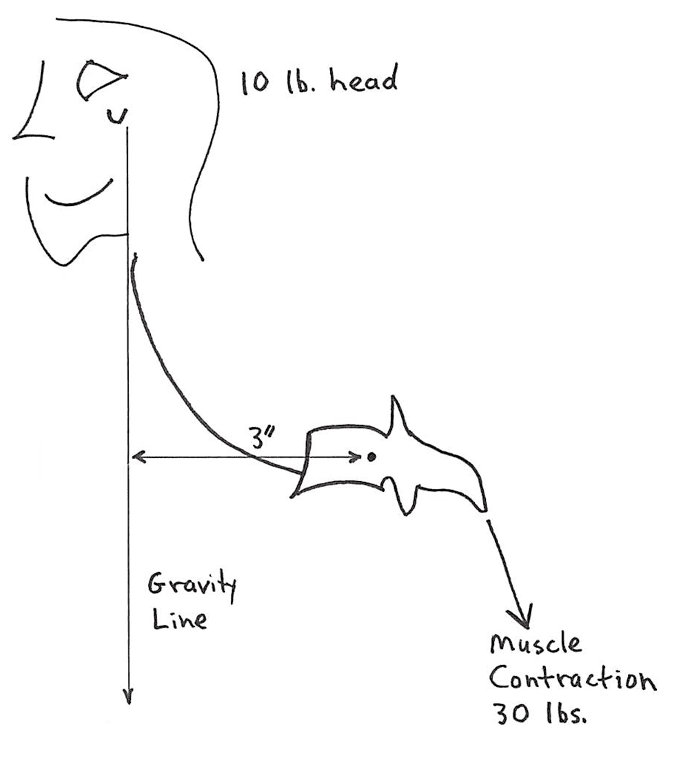

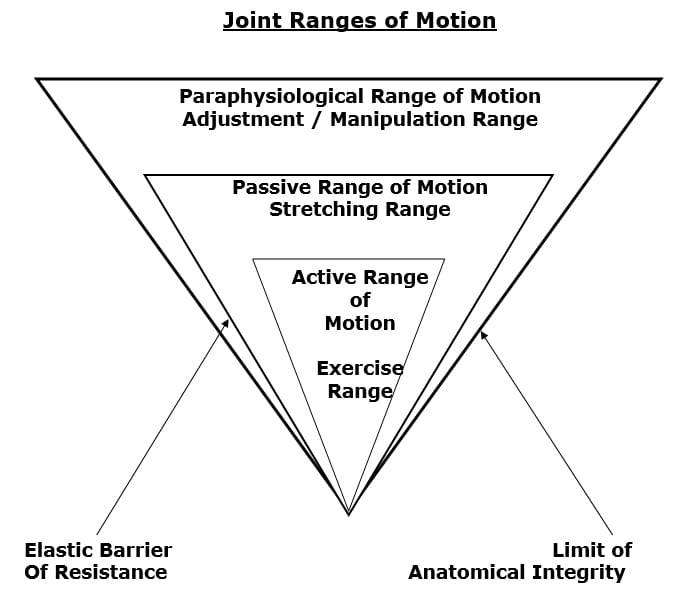

The aim of the thrust side-posture chiropractic manipulations of the spinal column was to restore the physiological motor unit movement. Rationales for using spinal manipulation in the treatment of low back pain and sciatica include:

- Reduction of a bulging disc

- Correction of disc displacement

- Release of adhesive fibrosis surrounding prolapsed discs or facet joints

- Release of entrapped synovial folds

- Inhibition of nociceptive impulses

- Relaxation of hypertonic muscles

- Unbuckling displaced motion segments

The study noted that:

“Active manipulations have more effect than simulated manipulations on pain relief for acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion.”

“At the end of follow-up a significant difference was present between active and simulated manipulations in the percentage of cases becoming pain-free (local pain 28% vs. 6%; radiating pain 55% vs. 20%).”

Active manipulations resulted in reduction of radiating pain and by a lower number of days on, and prescriptions of, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

“Patients receiving active manipulations enjoyed significantly greater relief of local and radiating acute LBP, spent fewer days with moderate-to-severe pain, and consumed fewer drugs for the control of pain.”

“No adverse events were reported.”

The authors concluded that chiropractic spinal “manipulations may relieve acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion.”

••••••••••

CONCLUDING POINTS

As a rule:

- Unless there are signs/symptoms of severe nerve compression, and/or cauda equina syndrome, patients suffering with discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica should be managed conservatively for a period of 4-6 weeks.

- If there is no improvement after a period of 4-6 weeks of conservative treatment, a CT and/or MRI is clinically warranted.

- If decompressive surgery is indicated, a delay of 4-6 weeks with conservative treatment does not adversely affect the surgical clinical outcome.

- Spinal x-rays are non-revealing for patients with discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica, and exposing them is the clinical discretion of the provider.

- If after 4-6 weeks of conservative treatment there is acceptable clinical improvement to justify continued conservative treatment, maximum conservative treatment benefit may not be achieved for a period of 3-12 months.

- Chiropractic spinal manipulation (adjusting) is as a rule both safe and effective in the treatment of discogenic radiculopathy/sciatica.

REFERENCES

- Fardon DR, Williams LA, Dohring EJ, Rothan SL, Sze GK; Lumbar Disc Nomenclature: Version 2.0: Recommendations of the Combined task forces of the North American Spine Society, the American Society of Spine Radiology, and the American Society of Neuroradiology; Spine Journal; 14; pp. 2525-2545.

- Kapandji IA; The Physiology of the Joints; Volume Three, The Trunk and the Vertebral Column; Churchill Livingstone; 1974.

- Deyo R, Mirza S; Herniated Lumbar Intervertebral Disk; New England Journal of Medicine; May 5, 2016; Vol. 374; No. 18; pp. 1763-1772.

- Ramsey RH; Conservative Treatment of Intervertebral Disk Lesions; American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, Instructional Course Lectures; Volume 11, 1954, pp. 118-120.

- Mathews JA, Yates DAH; Reduction of Lumbar Disc Prolapse by Manipulation; British Medical Journal; September 20, 1969; No. 3; pp. 696-697.

- Edwards BC; Low back pain and pain resulting from lumbar spine conditions: a comparison of treatment results; Australian Journal of Physiotherapy; 15:104, 1969.

- Turek S; Orthopaedics, Principles and Their Applications; JB Lippincott Company; 1977; page 1335.

- Kuo PP and Loh ZC; Treatment of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Protrusions by Manipulation; Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research; No. 215, February 1987, pp. 47-55.

- Cassidy JD, Thiel HW, Kirkaldy-Willis WH; Side posture manipulation for lumbar intervertebral disk herniation; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; February 1993; Vol. 16; No 2; pp. 96-103.

- Santilli V, Beghi E, Finucci S; Chiropractic manipulation in the treatment of acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion: A randomized double-blind clinical trial of active and simulated spinal manipulations; The Spine Journal; March-April 2006; Vol. 6; No. 2; pp. 131–137.