And The Potential Pitfalls Of Clinical Joint Immobilization

Back in 1984, orthopedic surgeon Sir James Cyriax, MD, reviewed The Concept Of Motion in his Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions (1). In this text, Dr. Cyriax carefully noted that harmful infections create tissue destruction, resulting in inflammation.

A current prevailing concept in explaining this observation is the body recognizes this inflammation and attempts to “wall off” the infectious pathogens by creating a fibrous response.

This is in fact in agreement with Dr. William Boyd who states in his pathology text (2):

“The inflammatory reaction tends to prevent the dissemination of infection. Speaking generally, the more intense the reaction, the more likely the infection to be localized.”

Physiologist and physician Arthur Guyton (3) provides support for this concept as well in his statement:

“One of the first results of inflammation is to ‘wall off’ the area of injury from the remaining tissues. This walling-off process delays the spread of bacteria or toxic products.”

Some interpret this type of response to mean that (in a world prior to the availability of antibiotics, inflammation, with reactive walling-off fibrosis to contain pathogens) it is desirable because it increases survivability of the host.

As explained by three vaunted researchers Cyriax, Boyd, and Guyton above, the trigger to the walling-off fibrosis response of the body is inflammation.

Problems appear to only seriously arise when the inflammatory trigger is non-infectious inflammation.

In such cases, excessive tissue fibrosis creates local impairments in biomechanical function.

This impairment in local biomechanical function affects performance, can generate pain, and accelerate degenerative changes. These impairments can adversely affect the patient for years or even decades.

Fortunately, abnormal tissue fibrosis can be minimized with early, persistent, controlled motion. Once established, abnormal tissue fibrosis can be improved with the use of a variety of motion applications.

Cyriax’s text (1) states the following:

“The excessive reaction of tissues to an injury is conditioned by the overriding needs of a process designed to limit bacterial invasion.

If there is to be only one pattern of response, it must be suited to the graver of the two possible traumas. However, elaborate preparation for preventing the spread of bacteria is not only pointless after an aseptic injury, but is so excessive as to prove harmful in itself. The principle on which the treatment of post-traumatic inflammation is based is that the reaction of the body to an injury unaccompanied by infection is always too great.” (Cyriax, p.14)

Cyriax finds support in the sports trauma text authored by physicians Steven Roy and Richard Irvin (4), who state:

“It is important to realize that the body’s initial reaction to an injury is similar to its reaction to an infection. The reaction is termed inflammation and may manifest macroscopically (such as after an acute injury) or at a microscopic level, with the latter occurring particularly in chronic overuse conditions.” (Roy, p. 125)

Additional support for these concepts from Cyriax and Roy/Irvin are the writings of physician I. Kelman Cohen and associates (5). In their 1992 text Wound Healing, these authors note:

“There are two important consequences of being a warm-blooded animal. One is that body fluids make optimal culture media for bacteria. It is to the animal’s advantage, therefore, to heal wounds with alacrity in order to reduce chances of infection.”

“The prompt development of granulation tissue forecasts the repair of the interrupted dermal tissue to produce a scar.” In addition to providing tensile strength, scars are believed to be a barrier to infectious migration.

The chronic nature of this scar tissue or fibrosis is expressed in the 1998 article by Thomas Melham and associates (6).

These authors note that post-traumatic scar tissue can cause pain with activity, pain on palpation, decreased range of motion, and loss of function, and that these problems are resistant to surgery and to conventional physical.

Excessive scar tissue contributes to chronic soft tissue dysfunction that cause significant disabilities and time lost from work or training activities, and these problems are often difficult to successfully treat. The authors extensively elaborate on the mechanical and neurological adverseness caused by connective tissue fibrosis, noting:

“Many athletes develop excessive connective tissue fibrosis (scar tissue) or poorly organized scar tissue in and around muscles, tendons, ligaments, joints, and myofascial planes as a result of acute trauma, recurrent microtrauma, immobilization, or as a complication of surgical intervention.”

“This can lead to soft tissue adhesions, tendonitis, tendonosis, fascial restrictions, and chronic inflammation or dysfunction which in many cases responds poorly to conventional treatments.”

These authors present an argument that carefully and precisely applied external forces “appear to stimulate connective tissue remodeling through resorption of fibrosis, along with inducing repair and regeneration of collagen secondary to fibroblast recruitment.”

Pain, Healing, and MOTION…

As noted above, abnormal tissue fibrosis can be minimized with early, persistent, controlled motion.

Once established, abnormal tissue fibrosis can be improved with the use of a variety of motion applications.

Support for the value in using motion to treat soft-tissue injuries has been throughout the literature for decades.

As an example, Beverly Hills neurosurgeon Emil Seletz, associated with the medical school at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), noted in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1958, the following, with respects to the management of whiplash soft-tissue injuries (7):

“During injury, hemorrhage within the capsular ligaments gives rise to swelling of the nerves and eventually adhesions between the dural sleeve and the nerve root; these factors give rise to symptoms that may be prolonged for months or even years after the injury.”

“In reviewing the types of treatment with a number of specialists in this field, it is found that, while therapy naturally varies to suit the individual need, it consists primarily of local heat in the form of hot wet packs and cervical traction, followed by very gentile massage and manual rotations.”

“The importance of a carefully planned scheme of treatment must be emphasized to the patient, and treatments must be religiously carried out daily during the first two or three weeks (and then about three times weekly), depending, of course, on the individual case.”

“Delay or faulty treatment leads to adhesions about the facets and scarring about the capsular ligaments, persistent spasm, congestive lymph edema, and fibrosis of muscles, swelling, and eventual adhesions of nerves within the nerve root canals.”

“The resultant faulty posture in neglected cases enhances the degeneration of the intervertebral disks, as well as spur formation in the lateral co-vertebral articulations, which on the roentgenogram has come to be known as traumatic arthritis.”

“I cannot too strongly emphasize the urgency of early and persistent therapy, always by a specialist in this field.”

“Occasionally, a patient is seen with persistent complaints of head, neck, and shoulder pain, who has had on surgical exposure persistent swelling and adhesions of several nerve roots within the dural sleeve of exit. It is most likely that early, persistent, and adequate therapy by those expertly trained in physical medicine will prevent most patients from developing a surgical condition.”

On this very same topic, Cyriax’s comments include a review of the 1940 primary research by ML Stearns (8), stating:

“Her (Stearns) main conclusion on the mechanics of the formation of scar tissue was that external mechanical factors, were responsible for the development of the fibrillary network into orderly layers.

Within four hours of applying a stimulus, an extensive network of fibrils was already visible around the fibroblasts; during the course of 48 hours this became dense enough to hide the cells almost completely: and in 12 days a heavy layer of fibrils had appeared.

At first the fibrils developed at random, but later they acquired a definite arrangement, apparently as a direct result of the mechanical factors.

Of these factors, movement is obviously the most important and equally obvious it is most effective and least likely to cause pain before the fibrils have developed an abnormal firm attachment to neighboring structures.

When free mobility was encouraged from the onset, the fibers in the scar were arranged lengthwise as in a normal ligament.

Gentle passive movements do not detach fibrils from their proper formation at the healing breach but prevent their continued adherence at normal sites.

The fact that the fibrils rapidly spread in all directions provides sufficient reason for beginning movements at the earliest possible moment; otherwise they develop into strong fibrous scars (adhesions) that so often cause prolonged disability after a sprain.” (Cyriax, p. 15)

Cyriax notes further:

“When pain is due to bacterial inflammation, Hilton’s advocacy of rest remains unchallenged and is today one of the main principles of medical treatment.

When, however somatic pain is caused by inflammation due to trauma, his ideas require modification.

When non-bacterial inflammation attacks the soft tissues that move, treatment by rest has been found to result in chronic disability, later, although the symptoms may temporarily diminish.

Hence, during the present century, treatment by rest has given way to therapeutic movement in many soft tissue lesions.

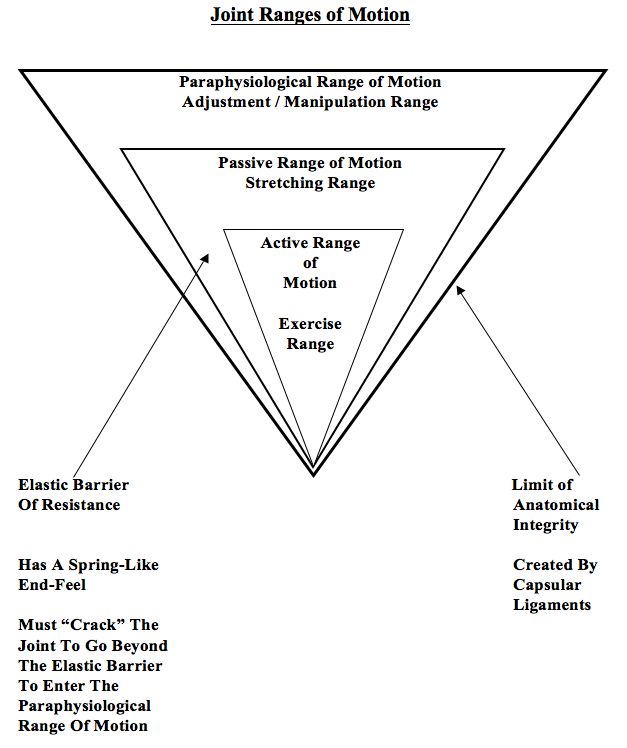

Movement may be applied in various ways: the three main categories are:

(a) active and resistive exercises:

(b) passive, especially forced movement: and

(c) deep massage.” (Cyriax, p.14)

“Tension within the granulation tissue lines the cells up along the direction of stress.

Hence, during the healing of mobile tissues, excessive immobilization is harmful.

It prevents the formation of a scar strong in the important direction by avoiding the strains leading to due orientation of fibrous tissue and also allows the scar to become unduly adherent, e.g. to bone.” (Cyriax, p.15

In 1983, sports physicians Steven Roy and Richard Irvin also note (4):

“The trauma, or initial lesion, leads to an increase of the friction that occurs between moving tissues as well as to a release of chemical mediators, both of which may start the inflammatory process.

This process may present macroscopically with a number of signs, particularly (a) pain (b) swelling, and (c) redness and warmth. However, microtrauma may not present with any of these signs, particularly during the early stages, even though the inflammation is proceeding at the microscopic level.” (p. 125)

“The injured tissues next undergo remodeling, which can take up to one year to complete in the case of major tissue disruption.

The remodeling stage blends with the later part of the regeneration stage, which means that motion of the injured tissues will influence their structure when they are healed.

This is one reason why it is necessary to consider using controlled motion during the recovery stage.

If a limb is completely immobilized during the recovery process, the tissues may emerge fully healed but poorly adapted functionally, with little chance for change, particularly if the immobilization has been prolonged.

Another reason for encouraging controlled motion is that any adhesions that develop will be flexible and will thus allow the tissues to move easily on each other.

Caution should be observed during the first two weeks, as mentioned previously, as the tensile strength of the tissues may be markedly reduced.” (p.127)

In 1986, physician John Kellett notes (9):

Acute inflammation is beneficial when one has acute infection. However, the “acute inflammatory phase of the body’s response to trauma is apparently of no benefit.”

“The micropathology of acute soft tissue trauma has been investigated. Healing of ligaments and soft tissue injuries in general has been shown to occur by fibrous repair (scar tissue) and not by regeneration of the damaged tissue.”

“Early mobilization, guided by the pain response, promotes a more rapid return to full activity.”

“Early mobilization, guided by the pain response, promotes a more rapid return to full functional recovery.”

“The collagen is remodeled to increase the functional capabilities of the tendon or ligament to withstand the stresses imposed upon it.”

“It appears that the tensile strength of the collagen is quite specific to the forces imposed on it during the remodeling phase: i.e. the maximum strength will be in the direction of the forces imposed on the ligament.”

Dr. Kellett summarizes the benefits of early mobilization following soft tissue injury as follows:

1) Improvement of bone and ligament strength, reducing recurrence of injury.

2) The strength of repaired ligaments is proportional to the mobility of the ligament, resulting in larger diameter collagen fiber bundles and more total collagen.

3) “Collagen fiber growth and realignment can be stimulated by early tensile loading of muscle, tendon, and ligament.”

4) Collagen formation is not confined to the healing ligaments, but adheres to surrounding tissues. The formation of these adhesions between repairing tissues and adjacent structures is minimized by early movement.

5) With motion, “joint proprioception is maintained or develops earlier after injury, and this may be of importance in preventing recurrences of injuries and in hastening full recovery to competitive fitness.”

6) The nutrition to the cartilage is better maintained with early mobilization.

7) Following this acute inflammatory phase and largely guided by the pain response of the patient, early mobilization is commenced, based upon the premise that the stress of movement on repairing collagen is largely responsible for the orientation and tensile strength of the tendons and ligaments.

Dr. Cohen (5) and associates also comment even further on the value of range of motion exercises in the management of soft tissue injury, by stating:

“During the phase of wound contraction, the active cellular process is locked into position by increasing amounts of rigid collagenous scar. Frequent, gentle exercise can be used to put an extremity joint through a full range of motion and keep the newly developing scar tissue stretched and remodeled. Frequent use of the range of motion exercises is important to keep the developing and contracting scar tissue from becoming a rigid, fixed scar contracture. Range of motion exercises concentrate on remodeling the newly laid collagen before it develops into a rigid scar contracture.” (p. 110)

In 1994, Halldor Jonsson and associates (10) performed surgical evaluations of 50 patients with chronic whiplash symptoms, showing a “high incidence of discoligamentous injuries in whiplash-type distortions.” The authors noted:

“The injured spinal segments had become increasingly stiffer over 5 years, which may reflect healing of unrecognized soft tissue injuries.”

“The most likely source of radicular symptoms is perineural scarring. Therefore, patients with neck distortions after traffic accidents should be mobilized early within the limits of pain to prevent scar transformation of hidden injuries.”

In 1996, orthopedic surgeon Joseph Buckwalter, MD, from the University of Iowa, adds to the concepts with the following points from an article published in the journal Hand Clinics (11):

1) Treatment of tissue injuries with prolonged rest delays recovery and can cause irreversible changes in tissue strength and function.

2) Early motion of tissue injuries maintains the structure and composition of normal bone, tendon, ligament, articular cartilage and muscle.

3) Immobilization of dense fibrous tissues (tendon, ligament, and joint capsule) causes the tissues to be weaker and stiffer.

4) Complete restoration of normal ligament insertion structure and mechanical properties require up to one year of activity, which can mean some patients may require a year of management following these injuries.

5) Ageing decreases the adaptive response to repetitive loading, indicating that older patients do not respond as well to the same treatment delivered to younger patients, and that older patients may require more treatment and have a worse prognosis for complete recovery.

6) Early motion during the repair and remodeling phases of healing can decrease or prevent adhesions.

In 1997, US President Bill Clinton tore the tendon of his quadriceps at the attachment to the patella. After surgical repair, President Clinton was put into a passive range of motion device to improve the timing and quality of healing of his injury.

The device used to treat Mr. Clinton was researched by Canadian orthopedic surgeon Robert Salter. Dr. Salter has published many primary research studies on the physiological effects of passive motion.

Much of this research is summarized in his 1993 book Continuous passive Motion, A Biological Concept for the Healing and Regeneration of Articular Cartilage, Ligaments, and Tendons; From Origination to Research to Clinical Applications (12).

It can be reasonably assumed that President Clinton received the best treatment in the world for his injuries. All indications reflect that he enjoyed a speedy and complete recovery.

Lastly, as presented here, an excellent review on The Concept Of Motion was published in the journal The Physician and Sports Medicine in 2000 by Pekka Kannus, MD, Ph.D. (13).

Dr. Kannus is chief physician and head of the Accident and Trauma Research Center and sports medicine specialist at the Tampere Research Center of Sports Medicine at the UKK Institute in Tampere, Finland. His article titled “Immobilization or Early Mobilization After an Acute Soft-Tissue Injury?” notes:

“Experimental and clinical studies demonstrate that early, controlled mobilization is superior to immobilization for primary treatment of acute musculoskeletal soft-tissue injuries and postoperative management.”

Prolonged inflammation may lead to excessive scarring. Therefore, early, effective treatment seeks to prevent prolonged inflammation and excessive scarring.

“The current literature on experimental acute soft-tissue injury speaks strongly for the use of early, controlled mobilization rather than immobilization for optimal heating.”

Experimentally induced ligament tears in animals heal much better with early, controlled mobilization than with immobilization.

“The superiority of early controlled mobilization has been especially clear in terms of quicker recovery and return to full activity without jeopardizing the subjective or objective long-term outcome.”

“Controlled experimental and clinical trials have yielded convincing evidence that early, controlled mobilization is superior to immobilization for musculoskeletal soft-tissue injuries. This holds true not only in primary treatment of acute injuries, but also in their postoperative management. The superiority of early controlled mobilization is especially apparent in terms of producing quicker recovery and return to full activity, without jeopardizing the long-term rehabilitative outcome. Therefore, the technique can be recommended as the method of choice for acute soft-tissue injury.”

Two Additional Supportive Studies…

Suportive Study #1

Early Mobilization of Acute Whiplash Injuries (14)

British Medical Journal

March 1986

In this study, 61 whiplash-injured patients were randomized to treatment with either “a period of immobility using a soft collar and simple analgesia before gradual mobilization” (standard treatment), or a alternative treatment involving “daily neck exercises and mobilization.” The authors concluded that:

“Results showed that eight weeks after the accident the degree of improvement seen in the actively treated group compared with the group given standard treatment was significantly greater for both cervical movement and intensity of pain.”

“Our results confirmed expectations that initial immobility after whiplash injuries gives rise to prolonged symptoms whereas a more rapid improvement can be achieved by early active management without any consequent increase in discomfort.”

Supportive Study #2

Early Intervention in Whiplash-Associated Disorders

A Comparison of Two Treatment Protocols (15)

Spine

July 15, 2000

This study was designed as a prospective randomized trial in 97 patients with a whiplash injury caused by a motor vehicle collision. Patients were randomly assigned to initial cervical collar or to early active mobilization. The authors concluded:

“In patients with whiplash-associated disorders caused by a motor vehicle collision, treatment with frequently repeated, active submaximal movements combined with mechanical diagnosis and therapy is more effective in reducing pain than a standard program of initial rest, recommended use of a soft collar, and gradual self-mobilization.”

“The main finding in this study was that active treatment of whiplash associated disorder resulted in a significantly greater pain reduction than standard [initial immobilization] treatment.”

“In patients with WAD caused by a motor vehicle collision, early treatment with frequently repeated active submaximal movements combined with mechanical diagnosis and therapy is more effective in reducing pain than treatment with initial rest, recommendation of a soft collar, and a gradual introduction of home exercises.”

Conclusions

The discussion and references above support the concept that adverse pathogens cause tissue destruction and subsequent inflammation. The body appears to respond in a manner to wall-off the area of inflammation by over healing the region with a fibrous response.

The fibrous response appears to be a physical barrier, reducing the ability of the pathogens to spread to other regions of the body, thereby improving the host’s chances for survival.

However, when inflammation is caused by non-infectious mechanisms, the same fibrotic tissue response occurs. In such cases, without infectious pathogens, the fibrotic tissue response is excessive, resulting in mechanical harm to the host.

This harmful tissue fibrosis is worsened with early immobilization of the affected tissues.

This tissue fibrosis is minimized with early persistent controlled mobilization.

Established harmful tissue fibrosis is best managed with specific controlled motion for purpose of adhesion rupture and remodeling. The motion to treat established harmful fibrotic tissue should be individualized to the needs of the patient.

Different fibrotic tissues respond optimally to different categories of controlled motion application:

1) Periarticular tissue fibrosis responds optimally to joint adjustments / specific line-of-drive manipulation.

2) Muscle fibrosis responds well to active resistive exercise.

3) Non-contractile tissue (tendon, fascia, ligament, etc.) fibrosis responds best to manually applied tissue friction.

Most patients have a combination of tissues that are adversely affected, depending on the mechanism of injury or stress.

Consequently, a combination of these applications of controlled motion, by someone who is expertly trained, is often required to achieve timely, efficient, and long-lasting clinical improvements.

REFERENCES

1) Cyriax, James; Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, Bailliere Tindall, Volume 1, eighth edition, 1982.

2) Boyd, William, Pathology, Lea and Febiger, 1952.

3) Guyton, Arthur, Textbook of Medical Physiology, Saunders, 1986.

4) Roy, Steven; Irvin, Richard; Sports Medicine: Prevention, Evaluation, Management, and Rehabilitation, Prentice-Hall, 1983.

5) Cohen, I. Kelman; Diegelmann, Robert F; Lindbald, William J; Wound Healing, Biochemical & Clinical Aspects, WB Saunders, 1992.

6) Melham TJ, Sevier TL, Malnofski MJ, Wilson JK, Helfst RK, Chronic ankle pain and fibrosis successfully treated with a new noninvasive augmented soft tissue mobilization technique (ASTM); Medicine Science Sports Exercise, June 1998; 30(3): 801-4.

7) Seletz E, Whiplash Injuries, Neurophysiological Basis for Pain and Methods Used for Rehabilitation; Journal of the American Medical Association, November 29, 1958, pp. 1750–1755.

8) Stearns, ML, Studies on development of connective tissue in transparent chambers in rabbit’s ear; American Journal of Anatomy, vol. 67, 1940, p. 55.

9) Kellett J, Acute soft tissue injuries–a review of the literature; Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. Oct. 1986;18(5):489-500.

10) Jonsson H, Cesarini K, Sahlstedt B, Rauschning W, Findings and Outcome in Whiplash-Type Neck Distortions; Spine, Vol. 19, No. 24, December 15, 1994, pp 2733-2743.

11) Buckwalter J, Effects of Early Motion on Healing of Musculoskeletal Tissues, Hand Clinics, Volume 12, Number 1, February 1996.

12) Salter R, Continuous Passive Motion, A Biological Concept for the Healing and Regeneration of Articular Cartilage, Ligaments, and Tendons; From Origination to Research to Clinical Applications, Williams and Wilkins, 1993.

13) Kannus P, Immobilization or Early Mobilization After an Acute Soft-Tissue Injury?; The Physician And Sports Medicine; March, 2000; Vol. 26 No 3, pp. 55-63.

14) Mealy K, Brennan H, Fenelon GCC; Early Mobilization of Acute Whiplash Injuries; British Medical Journal, March 8, 1986, 292(6521): 656-657.

15) Rosenfeld M, Gunnarsson R, Borenstein P, Early Intervention in Whiplash-Associated Disorders, A Comparison of Two Treatment Protocols; Spine, 2000;25:1782-1787.