More Evidence that Chiropractic Care Significantly Reduces the Use of Opioid Drugs

THE OPIATE/OPIOID PROBLEM

The government of the state of Oregon notes (1):

Opium is made from the poppy plant.

Opiates are compounds that can be purified directly from opium without modification. This includes morphine, codeine, methadone, and heroine.

Few people understand that dextromethorphan is an opiate. It is available in the United States without prescription in products such as NyQuil, Robitussin, TheraFlu, and Vicks. Dextromethorphan is primarily used as a cough suppressant.

Opioids are a synthetic form of opium that are made in a lab. Drug companies have created more than 500 different opioid molecules, including:

- OxyContin (oxycodone)

- Percocet (oxycodone)

- Vicodin (hydrocodone)

- Dilaudid (hydromorphone)

- Demerol

- Imodium

- Darvon

- Darvocet

- Opana

- Fentanyl

Fentanyl is legally prescribed as Ultiva, Sublimaze, and the Duragesic patch.

Both opiates and opioids are drugs known as “narcotics.” Narcotic means sleep-inducing or pain suppressing.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the United States Government note (2):

- 75% of the 92,000 drug overdose deaths in 2020 involved narcotics (opiates/opioids).

- Over 82% of these deaths involved synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl.

Side effects of opiates/opioids include insomnia, constipation, “jittery nerves,” and nausea (2). They cause life-threatening side effects such as shallow breathing and slowed heart rate, leading to loss of consciousness and death.

Opiates/opioids can cause addiction. They can make your brain and body believe the drug is necessary for survival. As you learn to tolerate the dose you’ve been prescribed, you may find that you need even more medication to relieve the pain. “More than 2 million Americans misuse opioids, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.”

According to the American Society of Anesthesiologists, heroin is an illegal and highly addictive form of opiate with no sanctioned medical use (3).

The Department of Justice of the United States government notes (4):

- In 2021, 107,622 lives were lost in the United States due to a drug overdose. This is an average of nearly 295 people per day.

- Drug overdoses are the leading cause of death for Americans ages 18-45; 66% of these overdose deaths were attributable to opioids, primarily by illicit fentanyl.

- Fentanyl “is the most dangerous drug threat facing our nation.”

- Fentanyl “is a deadly synthetic opioid that is being mixed into heroin, cocaine, and other street drugs.”

Cocaine is NOT an opiate. It is a powerfully addictive stimulant drug made from the leaves of the coca plant native to South America.

Physician Paul Offit, MD, in his 2017 book Pandora’s Lab: Seven Stories of Science Gone Wrong, notes (5):

- The dangers, addiction, and suffering attributed to the opium poppy have been recognized for 6000 years.

- Opium was used by the ancient Greeks, including Hippocrates and Galen. The ancient Romans also used opium. The Carthaginian general Hannibal used it to kill himself in 183 B.C.

- Arab merchants brought opium to China in the seventh century A.D. After Chinese citizens began to smoke opium, up to 90% of the population became addicted to it.

- Britain and China fought two Opium Wars between 1839 and 1860. China tried to stop the British importation of the drug that was enslaving their country.

- Americans consumed liquid opium, laudanum, including George Washington, Mary Todd Lincoln, and the wife of lawman Wyatt Earp.

- The German drug company Bayer began distributing heroin in 1900. It was marketed as being safe for children and pregnant women.

- In 1986, respected physician and pain specialist, Russell Portenoy, MD, opened the door for doctors to prescribe long-term, high-dose narcotics. He published his paper in the journal Pain (6). His article reported the stories of 38 people who were on high-dose narcotics, including OxyContin, for pain control. He assured physicians that there was little associated addiction and/or death. Dr. Portenoy reasoned that, “opioid maintenance therapy can be safe.” He encouraged physicians to get over their fear of painkillers, what he called “opiophobia.”

- In late 1995, the FDA approved Purdue Pharma’s timed-released version of OxyContin (time-released oxycodone). OxyContin became one of the most addictive narcotics ever sold, and the leading cause of accidental deaths in the United States.

Also, in 2017, the United States’ problem with opiates/opioids was quantified in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine in a study titled (7):

Prescription Opioid Use, Misuse, and Use Disorders in U.S. Adults

This survey used 51,200 adult subjects. The authors found:

- 8 million (37.8%) U.S. civilian, non-institutionalized adults used prescription opioids.

- 5 million adults misused opiate drugs (12.5%).

- 9 million US adults officially have an opiate use disorder.

- “More than one third of U.S. civilian, non-institutionalized adults reported prescription opioid use in 2015, with substantial numbers reporting misuse and use disorders.”

The authors note that the numbers they present are undoubtedly under representative of the opioid problem because they did not include an assessment of groups that are likely to take and to abuse these drugs, including:

- They did not survey homeless persons who were not living in shelters.

- They did not survey active-duty military personnel.

- They did not survey anyone in jail or other institutions.

An important 2018 study on the topic of opiates/opioids was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, titled (8):

Effect of Opioid vs Non-opioid Medications on Pain-Related Function in Patients with Chronic Back Pain or Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis Pain:

This study was a Randomized Clinical Trial that involved 234 subjects. Eligible patients had moderate to severe chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain despite analgesic use. Chronic Pain was defined as pain nearly every day for 6 months or more. The authors state:

“Rising rates of opioid overdose deaths have raised questions about prescribing opioids for chronic pain management.”

“Because of the risk for serious harm without sufficient evidence for benefits, current guidelines discourage opioid prescribing for chronic pain.”

“Studies have found that treatment with long-term opioid therapy is associated with poor pain outcomes, greater functional impairment, and lower return to work rates.”

“Treatment with opioids was not superior to treatment with non-opioid medications for improving pain-related function over 12 months. Results do not support initiation of opioid therapy for moderate to severe chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain.”

This study was reviewed by the Back Letter in an article titled (9):

Landmark Trial Punctures the Myth That Opioids Provide Powerful Relief of Chronic Pain

The Back Letter makes the following points:

“The deadly opioid overtreatment epidemic picked up steam in the late 1980s and early 1990s with the misguided notion that opioids are painkillers that can be used safely and effectively in the long-term treatment of chronic back pain—or other forms of noncancer chronic pain.”

“The intervening years—and as many as 300,000 deaths in the related opioid overdose epidemic—have rebutted the idea that opioids can be used safely on a mass basis.”

“Opioids are perceived as strong pain relievers, but our data showed no benefits of opioid therapy over non-opioid medication therapy for pain.”

“The data do not support opioids’ reputation as ‘powerful painkillers.’”

“This is an impressive study…. It is the first clinical trial comparing opioid and non-opioid medications with long-term follow-up. It provides strong evidence that opioids should not be the first line of treatment for chronic musculoskeletal pain.”

“Opioids are not achieving the benefits for which they are marketed. And everyone is now well aware of the adverse effects of opioids.”

Chiropractic v. Opiates/Opioids

In 2007, a study was published in the journal Clinical Therapy, titled (10):

Narcotic Drug Use Among Patients with Lower Back Pain in Employer Health Plans

The study sample included 13,760 patients with low back pain (LBP) due to mechanical causes. Almost half of the patients with LBP (45%) used narcotic drugs. Pertaining to chiropractic, the authors noted:

“Patients with LBP who received chiropractic services were less likely to use narcotic drugs. Chiropractic care appears to be a substitute treatment to pain medication and other health care services in patients with LBP due to the different sequence of services for pain treatment.”

In 2014, a study was published in the journal Neurology, titled (11):

Opioids for Chronic Non-cancer Pain:

A Position Paper of the American Academy of Neurology

The author, Gary Franklin, MD, notes:

- There is no evidence from clinical trials that opioids could be safely and effectively used in patients with chronic non-cancer pain.

- Studies show that long-term use of opioid pain drugs causes them to lose their analgesic effect because of drug tolerance or opioid-induced hyperalgesia.

- The use of opioid drugs on low back-injured workers does not cause meaningful improvement in pain and function.

- When workers are given opioids for low back injuries, there is a doubling of the development of long-term disability.

- The author recommends “against use of opioids for mild to moderate pain conditions, such as chronic musculoskeletal conditions, headache, and fibromyalgia.”

- “In the long run, the use of opioids chronically for most routine conditions, such as chronic low back pain, chronic headaches, or fibromyalgia, will not prove to be worth the risk.”

- “Cognitive–behavioral therapy, structured exercise, spinal manipulation, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation, although proven to be moderately effective in treating subacute and chronic low back pain, are often either not available or not adequately funded.”

- “The risks for chronic opioid therapy for some chronic conditions such as headache, fibromyalgia, and chronic low back pain likely outweigh the benefits.”

In 2018, a study was published in The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, titled (12)

Association Between Utilization of Chiropractic Services for Treatment of Low-Back Pain and Use of Prescription Opioids

The authors used a retrospective cohort design to analyze health insurance claims of 6,868 low back pain subjects from New Hampshire. In 2015, New Hampshire had the second-highest age adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths in the United States, a 31% increase from the previous year and more than double the national rate. The subjects were aged 18–99 years. The authors note:

“More aggressive pain management efforts that began in the 1990s have led to an epidemic of prescriptions for opioid pain medications in the U.S.”

“More than 650,000 opioid prescriptions are dispensed per day in the United States.”

“One out of five patients with non-cancer pain or pain-related diagnoses is prescribed opioids in office-based settings.”

“There is little evidence that opioids improve chronic pain, function, or quality of life.”

“Among U.S. adults prescribed opioids, 59% reported having back pain.”

“Among New Hampshire adults with office visits for non-cancer low-back pain, the adjusted likelihood of filling a prescription for an opioid analgesic was 55% lower for recipients of services provided by doctors of chiropractic compared with non-recipients.”

“Pain management services provided by doctors of chiropractic may allow patients to use lower or less frequent doses of opioids, leading to lower costs and reduced risk of adverse effects.”

“[Chiropractic care] could exert a positive impact on patients with low-back pain by reducing unnecessary care, lowering costs, and improving safety.”

“Pain relief resulting from services delivered by doctors of chiropractic may allow patients to use lower or less frequent doses of opioids, leading to reduced risk of adverse effects.”

Also, in 2018, the journal Pain Medicine published a study titled (13):

Opioid Use Among Veterans of Recent Wars Receiving Veterans Affairs [VA] Chiropractic Care

The authors are from Yale School of Medicine, School of Medicine Boston University, and University of Massachusetts Medical School. The VA began providing chiropractic services on-site in 2004 and has expanded implementation each year thereafter. In the VA, chiropractic patients are seen overwhelmingly for low back and/or neck musculoskeletal pain conditions. In private sector populations, increases in chiropractic care is correlated with reduced opioid use.

A 2016 VA Health Services Research conference “recommended broader uptake of a group of evidence-based nonpharmacological therapies,” including spinal manipulation, massage, acupuncture, exercise, and patient education, which “are the core components of multimodal chiropractic care in the VA.” The authors state:

“As reduction in opioid use remains a national priority, a better understanding of the relationship between opioid use and chiropractic services is needed to inform research and policy efforts aimed to assess and/or optimize the delivery of chiropractic care in the VA.”

“Apart from the potential to reduce pain and improve function in patients with musculoskeletal conditions, chiropractic care may have an impact on opioid use in such patients.”

“Chiropractic care is more likely to be a replacement for, rather than an addition to, opioid therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions in the VA.”

“Our results, along with the previous literature, suggest that expanding access to chiropractic care should be a key policy consideration for the VA, congruent with national initiatives aimed to increase the use of evidence-based nonpharmacological treatments for chronic musculoskeletal pain.”

In 2019, a study was published in the journal BMJ Open titled (14):

Observational Retrospective Study of the Initial Healthcare Provider for New-onset Low Back Pain with Early and Long-term Opioid Use

The authors examined the association of initial conservative therapy provider treatment (chiropractors, acupuncturists, physical therapists) on opioid use in a national sample (216,504) of individuals with a new-onset low back pain (LBP). The most frequent initial conservative provider seen was a chiropractor. The authors note:

“One of the most common conditions for which opioids are prescribed is low back pain (LBP).”

“Comparisons of the treatment patterns of primary care physicians and conservative therapists (defined as chiropractors, physical therapists, acupuncturists) suggest that the use of conservative therapies for LBP may decrease the likelihood of opioid use.”

“For early opioid use, patients initially visiting chiropractors had 90% decreased odds.”

“Patients who received initial treatment from chiropractors or physical therapists had decreased odds of short-term and long-term opioid use compared with those who received initial treatment from primary care physicians.”

- Chiropractic: 90% reduction

- Physical Therapy: 85% reduction

“Initial visits to chiropractors or physical therapists are associated with substantially decreased early and long-term use of opioids.”

In 2020, a study was published in the journal Pain Medicine, titled (15):

Association Between Chiropractic Use and Opioid Receipt Among Patients with Spinal Pain

The authors are from Yale School of Medicine. This meta-analysis used 6 studies, 5 that focused on back pain and 1 on neck pain: “All six studies (62,624 patients) provided sufficient data and were judged similar enough to be pooled for meta-analysis.” Studies that evaluated spinal manipulation delivered by providers other than chiropractors were excluded. The authors note:

“Chiropractors predominantly manage spinal conditions, with back conditions being the most common reason to seek chiropractic care.”

“Chiropractors provide many of the non-pharmacological treatments recommended by clinical practice guidelines for spinal pain, including spinal manipulation, patient education, exercise, acupuncture, and massage.”

“Ideally, non-pharmacological therapies including multimodal chiropractic care are utilized as frontline treatments to ultimately avoid the prescription of opioids, which are associated with poor outcomes for low back pain and chronic pain.”

“The main finding of the review was that all included studies demonstrated a negative association between use of chiropractic care and opioid prescription receipt.”

“The current study adds to the small but increasing body of evidence demonstrating that access to and utilization of chiropractic services are negatively associated with opioid use.”

“This review demonstrated an inverse association between chiropractic use and opioid receipt among patients with spinal pain.”

“Chiropractic users had 64% lower odds of receiving an opioid prescription than nonusers.”

Also, in 2020, a study was published in the journal Pain Medicine, titled (16):

Impact of Chiropractic Care on Use of Prescription Opioids in Patients with Spinal Pain

The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of chiropractic utilization upon use of prescription opioids among patients with spinal pain. It involved 101,221 subjects, aged 18-84 years, from Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire. Subjects were followed for up to six years. The authors note:

“Among patients with spinal pain disorders, for recipients of chiropractic care, the risk of filling a prescription for an opioid analgesic over a six-year period was reduced by half, as compared with non-recipients.”

“Among those who saw a chiropractor within 30 days of being diagnosed with a spinal pain disorder, the reduction in risk was greater as compared with those who visited a chiropractor after the acute phase had passed.”

“Multiple opportunities for patient–doctor interaction may allow the chiropractor to review clinical progress, advise on home exercise, ergonomics, and other self-management strategies, and provide reassurance, all of which may help improve outcomes and reduce the need for medication.”

“[There is] accumulating evidence for increased utilization of chiropractic services as an upstream strategy for reducing dependence upon prescription opioid medications.”

In 2022, a study was published in the Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, titled (17):

Associations Between Early Chiropractic Care and Physical Therapy on Subsequent Opioid Use Among Persons with Low Back Pain

The objective of this study was to estimate the association between early use of physical therapy (PT) or chiropractic care and opioid use in individuals with low back pain (LBP). It assessed 40,929 patients with LBP. The authors note:

“Nearly 80% of opioid users take their pain medication long-term.”

“Chiropractors have historically focused on manipulation to improve function of the spine to alleviate back pain.”

“The use of chiropractic care within 30 days of LBP diagnosis was associated with diminished use of opioids in the short term and, in particular, the long term, in which the risk of long-term opioid use was almost cut in half.”

“Chiropractic care was associated with substantial reduction in likelihood of any opioid use and long-term opioid use [by 44%].”

Also, in 2022, a study was published in the journal Chiropractic & Manual Therapies, titled (18):

Association Between Chiropractic Care and Use of Prescription Opioids Among Older Medicare Beneficiaries with Spinal Pain

This retrospective observational study examined 55,949 Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with spinal pain, of whom 9,356 were recipients of chiropractic care and 46,593 were non-recipients. The authors note:

“Opioid analgesics continue to be widely prescribed for spinal pain despite current evidence-based clinical guidelines that identify non-pharmacological therapies as the preferred first-line approach.”

“Chiropractic care is an alternative to opioid analgesia for spinal pain.”

“The adjusted risk of filling an opioid prescription within 365 days of first office visit was 56% lower among recipients as compared to nonrecipients.”

Among early recipients of chiropractic care, the reduction of filling an opioid prescription was 62% lower as compared to non-recipients.

“Our results suggest that—in addition to lower cost and more efficient utilization of clinical resources—early chiropractic care for spinal pain is also associated with improved patient safety as compared to conventional medical care, at least with regard to use of opioids.”

“Among older Medicare beneficiaries with spinal pain, use of chiropractic care is associated with significantly lower risk of filling an opioid prescription.”

SUMMARY

A bold but logical conclusion from these presented studies is that all patients of all age groups with spine pain syndromes should try chiropractic care prior to using opiate/opioid pain drugs.

REFERENCES

- https://www.oregon.gov/adpc/pages/opiate-opioid.aspx; accessed February 23, 2023.

- https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/basics/index.html; accessed February 23, 2023.

- https://www.asahq.org/madeforthismoment/pain-management/opioid-treatment/what-are-opioids/; accessed February 23, 2023.

- https://www.justice.gov/opioidawareness/opioid-facts; accessed February 23, 2023.

- Offit PA; Pandora’s Lab: Seven Stories of Science Gone Wrong; National Geographic; 2017.

- Portenoy RK, Foley KM; Chronic use of opioid analgesics in non-malignant pain: report of 38 cases; Pain; May 1986; Vol. 25; No. 2; pp. 171-186.

- Han B, Wilson M. Compton WM, Blanco C, Crane E, Lee J, Jones CM; Prescription Opioid Use, Misuse, and Use Disorders in U.S. Adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health; Annals of Internal Medicine; September 2017; Vol. 167; No. 5; pp. 293-301.

- Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, Jensen AC, DeRonne B, Goldsmith ES, Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Noorbaloochi S; Effect of Opioid vs Non-opioid Medications on Pain-Related Function in Patients With Chronic Back Pain or Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis Pain: The SPACE Randomized Clinical Trial; Journal of the American Medical Association; March 6, 2018; Vol. 319; No. 9; pp. 872-882.

- Back Letter; Landmark Trial Punctures the Myth That Opioids Provide Powerful Relief of Chronic Pain; 32; No. 7; July 2017.

- Rhee Y, Taitel MS, Walker DR, Lau DT; Narcotic drug use among patients with lower back pain in employer health plans: A retrospective analysis of risk factors and health care services; Clinical Therapy; 2007; Vol. 29; Supplemental; pp. 2603–2612.

- Franklin GM; Opioids for Chronic Non-cancer Pain: A Position Paper of the American Academy of Neurology; Neurology; September 30, 2014; Vol. 83; pp. 1277-1284.

- Whedon JM, Toler AWJ, Goehl JM, Kazal LA; Association Between Utilization of Chiropractic Services for Treatment of Low-Back Pain and Use of Prescription Opioids; The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine; June 2018; Vol. 24; No. 4; pp. 552-556.

- Lisi AJ, Corcoran KL, DeRycke EC, Bastian LA, Becker WC and 11 more; Opioid Use Among Veterans of Recent Wars Receiving Veterans Affairs Chiropractic Care; Pain Medicine; September 1, 2018; Vol. 19; Supplemental; pp. S54–S60.

- Kazis LE, Ameli O, Rothendler J, Garrity B, Cabral H, McDonough C, Carey K, Stein M, Sanghavi D, Elton D, Fritz J, Saper R; Observational Retrospective Study of the Initial Healthcare Provider for New-onset Low Back Pain with Early and Long-term Opioid Use; BMJ Open; September 2019; Vol. 9; No. 9; e028633.

- Corcoran KL, Bastian LA, Gunderson CG, Steffens C, Brackett A, Lisi AJ; Association Between Chiropractic Use and Opioid Receipt Among Patients with Spinal Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis; Pain Medicine; February 1, 2020; Vol. 21; No. 2; pp. e139-e145.

- Whedon JM, Toler AWJ, Kazal LA, Bezdjian S, Goehl JM, Greenstein J; Impact of Chiropractic Care on Use of Prescription Opioids in Patients with Spinal Pain; Pain Medicine; December 25, 2020; Vol. 21; No. 12; pp. 3567-3573.

- Acharya M, Chopram D, Smith AM, Fritz JM, Martin BC; Associations Between Early Chiropractic Care and Physical Therapy on Subsequent Opioid Use Among Persons with Low Back Pain in Arkansas; Journal of Chiropractic Medicine; June 2022; Vol. 21; pp. 67-76.

- Whedon JM, Uptmor S, Toler AJW, Bezdjian S, MacKenzie TA, Kazal LA; Association Between Chiropractic Care and Use of Prescription Opioids Among Older Medicare Beneficiaries with Spinal Pain: A Retrospective Observational Study; Chiropractic & Manual Therapies; January 31, 2022; Vol. 30; No. 1.

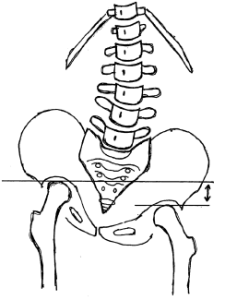

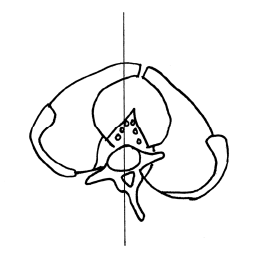

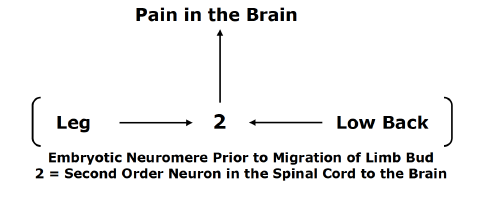

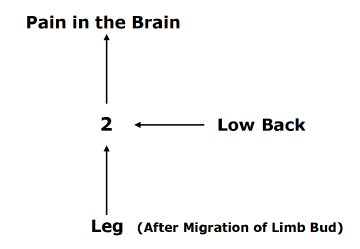

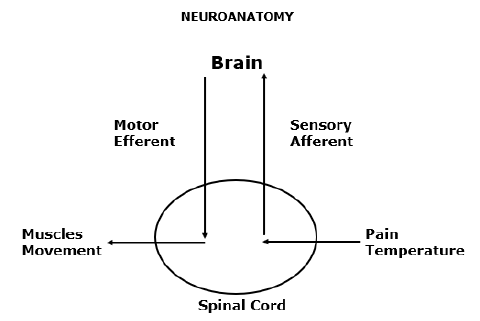

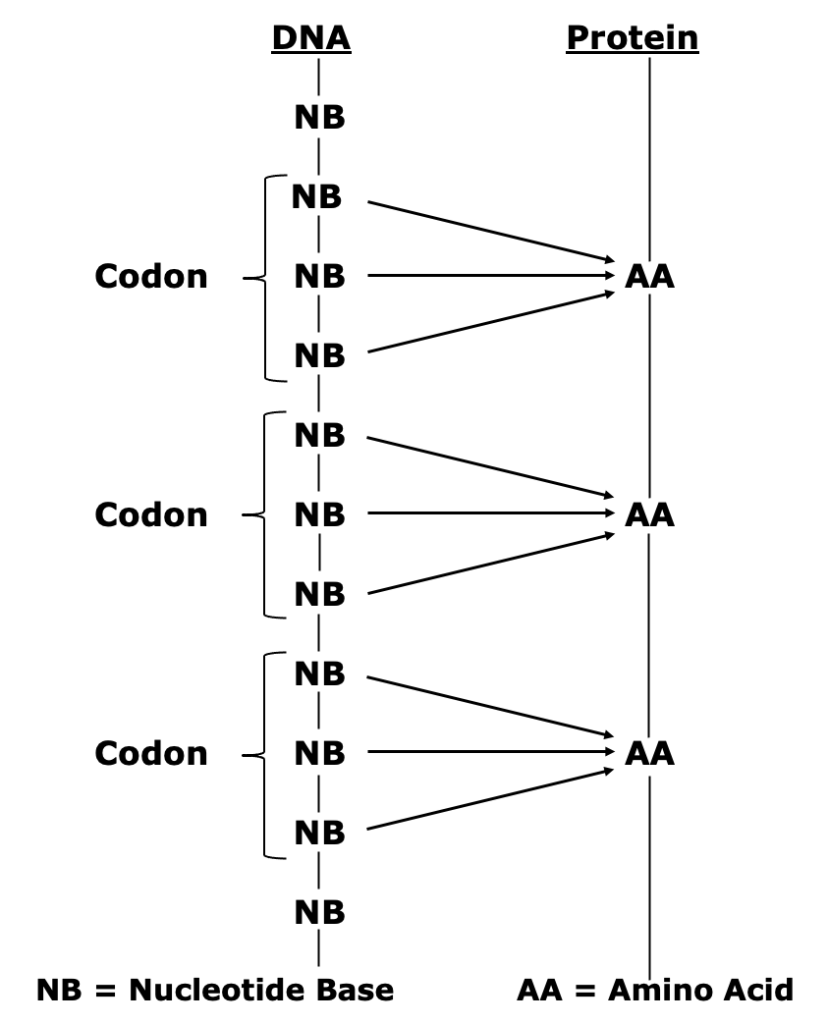

The nerves of the legs and low back arise from the same embryologic neuromere. The nerves of the legs and low back use the same second order neuron in the spinal cord to send the pain electrical signal to the brain. With the growth of the fetus, the limb bud migrates, but it maintains its embryotic neuromere.

The nerves of the legs and low back arise from the same embryologic neuromere. The nerves of the legs and low back use the same second order neuron in the spinal cord to send the pain electrical signal to the brain. With the growth of the fetus, the limb bud migrates, but it maintains its embryotic neuromere.

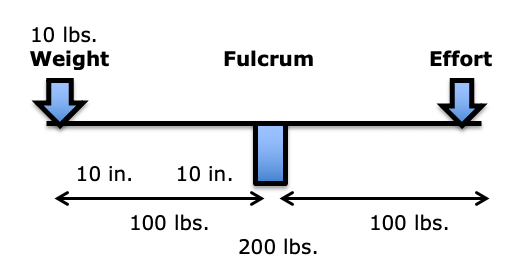

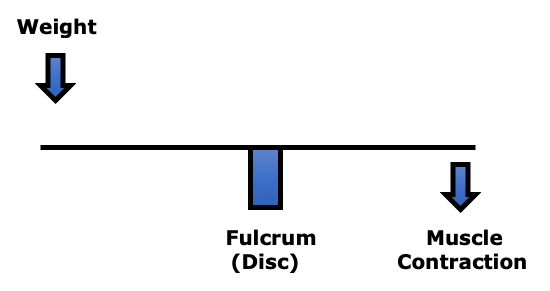

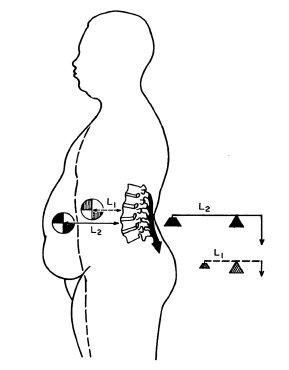

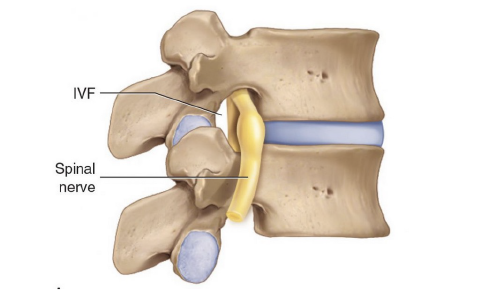

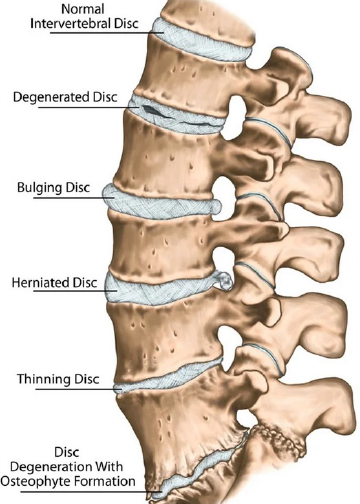

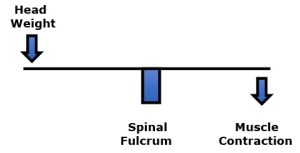

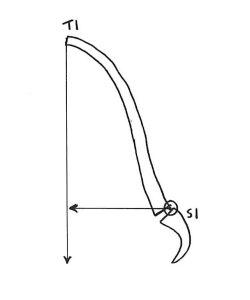

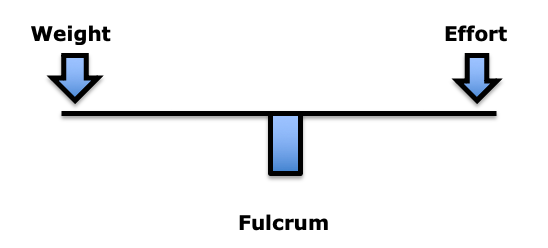

In the first-class lever mechanical system, the fulcrum is between the weight and the effort. The fulcrum is the site of greatest mechanical stress.

In the first-class lever mechanical system, the fulcrum is between the weight and the effort. The fulcrum is the site of greatest mechanical stress.